Mining has been at the heart of the Australian economy and has played a key role in shaping modern day Australia. For an industry that has soared to great heights, could the Australian people benefit more from its success? Norway’s oil taxation model has been a solution for its people, developing a sovereign wealth fund that redistributes natural resource wealth to its citizens, providing a possible path for similar success in Australia. Though as the mining sector grapples with global uncertainty, a taxation plan on super profits or resource rent tax could see the industry hurt more than Australia gains.

Australia’s mining industry generated $253.2 billion in profits in 2024, yet government revenue captured remains modest relative to this windfall. By comparison, Norway provides a globally respected model for ensuring its natural resources benefit the broader population, not just corporate shareholders.

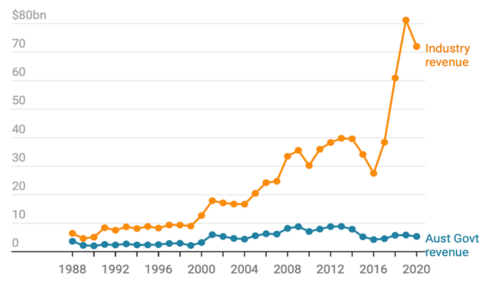

Figure 1: Australian Industry and Government Revenue From Oil and Gas

Source: Australian Institute

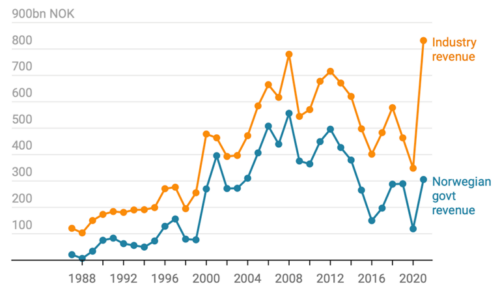

Figure 2: Norwegian Industry and Government Revenue From Oil and Gas

Source: Australian Institute

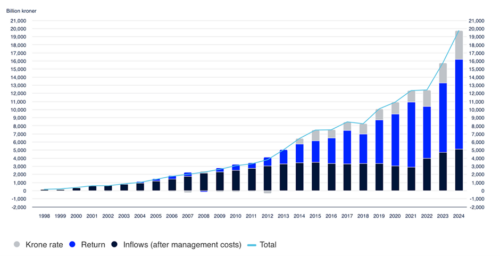

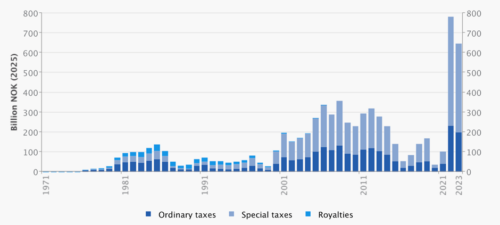

Since the discovery of North Sea oil, Norway has applied a 78% effective tax rate on petroleum profits through a combination of a 22% corporate tax and a 56% special petroleum tax. In 2022 alone, this generated NOK 1,457 billion (AUD 221 billion) in government revenue from petroleum activities. Crucially, these earnings are invested into the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), now valued at over AUD 2.2 trillion, ensuring future generations benefit long after oil fields are depleted.

Figure 3: Market Value of The Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund

Source: NBIM

Norway’s approach has not deterred investment as multinational companies continue to operate under this high-tax model because of stable policies, transparent governance, and access to valuable resources. Australia, with foreign-owned firms holding 86% of mining profits, risks losing long-term national benefits under its comparatively low royalty and tax regime.

Figure 4: Net Government Cash Flows From Petroleum Activities (1971 – 2023)

Sources: Statistics Norway

By introducing a resource rent tax or super profits tax linked to commodity prices and directing proceeds into a sovereign wealth fund, Australia can mirror Norway’s success. This would not only stabilise the national budget, while supplementing it during commodity downturns, but also fund essential public services, infrastructure, and environmental projects. This provides a channel for Australia’s finite mineral wealth to improve quality of life for current and future Australians.

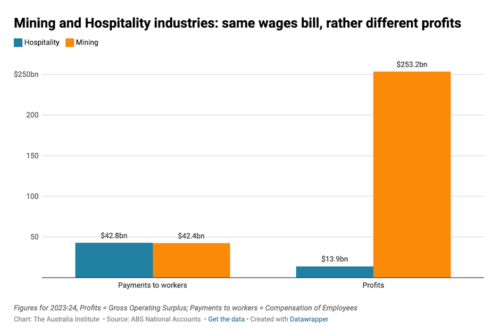

In an industry that has generated hundreds of billions in revenue annually, and has benefited from super profits particularly during the mining boom in the 2010s, the Australian government has seen disproportionately low levels of earnings captured from the sector. . In 2024, the mining industry distributed wages similar to the hospitality industry despite earning 18 times the profits, reaching $253.2 billion. This stark contrast highlights an opportunity for the government to capture a fair share of wealth. For example, a 40% super profits tax can increase the fiscal balance significantly by $101.28 billion. The taxation can redirect wealth to the public and protect Australians from price volatility in the market.

Figure 5: Mining and Hospitality industries: same wages bill, rather different profits

Source: Australian Institute

Implementing higher mining royalties provides a clear and beneficial strategy for Australia to ensure that the extraction of finite resources yields substantial public welfare relative to the significant profits produced . For instance, tax revenue could enhance the affordability of childcare services, which remains a barrier to workforce participation. Moreover, the recent $1 billion pledge to expand mental health access also reflects the need for funding from our public healthcare system. From a long-term perspective, taxes could be utilised for green investments to mitigate the environmental damage from mining or to fund public transport infrastructure projects, such as the long-awaited Airport Railway for Melburnians.

In addition to increasing government revenue, stronger taxation on the mining industry can capture the upside gains of growing commodity prices currently flowing overseas to foreign-owners of Australia’s mining companies . While foreign mining companies have benefited from increased prices from global conflicts like the Ukraine- Russia affairs, domestic energy users have seen their costs rise in response to international market pressures. Yet, the lack of royalties or super profit taxes prevents the returns from these inflated prices from being redirected into national welfare. A more potent and direct tax scheme would ensure a fair distribution of wealth and resources, while shielding domestic consumers from economic volatility driven by global affairs.

The Minerals council described the 2.75 royalty imposed on Victorian Gold in 2020 as a “Job-wrecking mining tax grab”. This represents a counterargument that increasing mining royalties can have a distortionary effect on production decisions and hence the profitability of the industry. A fixed royalty rate can be problematic when the government is receiving the same share of revenue even when market prices are high, and companies will need to pay this rate even when market prices are low. Alternatively, a variable royalty rate can be applied by calculating a percentage of the value of the mineral and requires a recognised market with published prices, which may not exist for certain minerals. These royalties add to the baseline of the mining sector, imposing a burden on decision-making and revenue.

If higher royalties were to impact the revenue of mining projects, the extent of the risk to the mining industry will largely depend on the elasticity of Australia’s mining supply in response to the royalty. This suggests that an elastic supply curve would lead to a significant reduction in production and consequently a reduction in profits for mining companies.

Figure 6: Fosterville Gold Mine, Victoria

Source: Mining Technology

Since mining royalties have a direct impact on income, the resulting decrease must be considered when determining cut-off grade curves. This suggests that to maintain profitability after a royalty increase, mining projects may reduce exploration, as operations will shift toward exploiting minerals at a higher cut-off grade. This reduction in exploration and overall profitability will likely disincentive investment in the mining industry, as lower returns reduce the motivation to invest in new projects. An exploration offset could potentially be the solution to removing any distortionary effects a higher royalty would have on the mining sector, though at a cost of stagnant investment.

While mining royalties can have positive implications on public welfare, there are also drawbacks to increasing mining royalties that the government must consider when implementing an effective tax scheme. By introducing a resource rent tax or super profits tax, Australia has the potential to emulate Norway’s successful approach. Though ensuring the industry is equipped to manage both an increase in the tax payments, whilst managing slowing demand from major trading partners is key to its success. With targeted policies, Australia can continue to capitalise on its rich mineral resources and support the long-term growth of its world-leading mining sector.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.