Amidst the expanse of the Persian Gulf, Dubai stands as a testament to urban innovation, often hailed for its rapid developments–growing into a bustling metropolis built from nothing. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Dubai was a fishing and pearl centre home to only around 20,000 inhabitants. Upon discovering oil, however, the newly independent United Arab Emirates (UAE) would grow rapidly. Sheikh Rashid (1912-1990), the ruler of Dubai, channelled oil revenue from Abu Dhabi into public infrastructure and works, rapidly turning Dubai into a major commercial hub. By the 1990s, Dubai saw an immense increase in tourism, developing a massive expatriate population and a unique, futuristic skyline–a tribute to the nation’s rapid development and innovation.

Today, Dubai still reaps the benefits of oil revenue. The city’s luxury reputation has been subject to several criticisms, however, drawing a stark contrast between the country’s overt glamour and its dark, unsustainable foundations. Now at a crossroads, the future of Dubai and the UAE as a whole is threatened: will the Gulf Tiger continue its growth and become even more dominant, or will Dubai fade away as quickly as it rose?

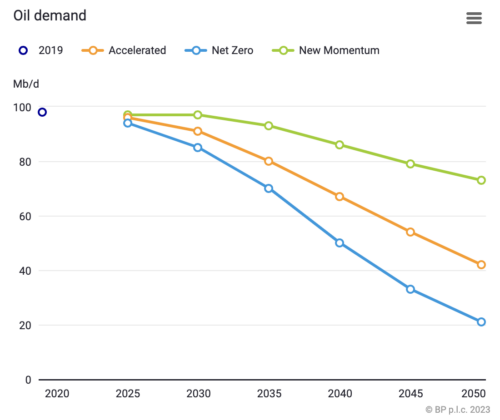

Global trends have called Dubai’s economic sustainability into question. With a world seeking alternatives to oil, a shift away from oil is imperative in maintaining Dubai’s position in the Gulf.

According to the International Energy Agency, while demand for oil from the petrochemicals industry is expected to remain, annual demand is expected to decline from 2.4 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2023 to just 0.4 mb/d in 2028. Furthermore, Dubai faces competition within this realm from countries outside of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), such as the United States of America (USA), Brazil and Guyana. BP stated that demand for oil is expected to peak sometime around 2030, followed by a steep decline.

Source: bp: Figure 1. Forecasted decrease in oil demand

The UAE has invested in several industries in order to diversify its economy. Dubai is becoming a top financial hub and has been trying to attract international technology companies and start-ups. Certainly, this has been effective to an extent. The UAE’s economy is expected to outpace that of the other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, owing to growth in non-oil industries. Rashed Al Blooshi, undersecretary at Abu Dhabi’s Department of Economic Development, states that investments in non-oil sectors have benefited Abu Dhabi’s formerly oil-reliant GDP and will help “sustain the growth.”

Similar reforms benefit Dubai, which is significantly less reliant on oil than Abu Dhabi. Mishrif and Kapetanovic state that Dubai’s diversification strategy involves the city using oil revenue to invest in other industries. Dubai’s economic model emphasises state-led industries, unhindered access to foreign capital and labour, reinvestment into local projects, and, more recently, its aforementioned diversification strategy.

While Dubai’s resilience in terms of its economic sustainability in the face of future adversity is yet to be known, its economic model has shown mixed results in previous crises. In 2009, Dubai World, which manages the large portfolio of the Government of Dubai, announced a moratorium on its debts amounting to US$60 billion. At the same time, property prices were falling around the city. This crisis almost left the famous World Islands incomplete. Oil came to the rescue, however, following a $20 billion bailout from oil-rich Abu Dhabi, which prevented numerous state-owned companies in Dubai from defaulting. Given that Dubai’s economic model incurs high levels of debt solely insured by oil money, a post-oil world will undoubtedly severely hurt Dubai if it is unable to recreate its growth in a diversified economy.

Many other issues threaten Dubai’s economic sustainability. The UAE dirham (AED) maintains a peg with the US dollar. The dirham is, therefore, subject to the ebb and flow of American monetary policy, even if it demerits the dirham. Dubai has also long relied on illicit funds in its economy. The European Union still lists the UAE as a high-risk country due to money laundering and terrorism financing.

Perhaps most dire is the necessity of Dubai’s reputation in receiving foreign direct investments. The UAE reportedly spent 20 million US dollars in 2018 to lobby firms and media outlets to promote the UAE’s image. Press freedom and other civil liberties are also cracked down on, with any criticism being aggressively suppressed. Dubai relies on foreign investment and expertise for its diversification strategy in its pivot from oil. Given the system’s over-reliance on the suppression of dissent, among other hindering factors, maintaining Dubai’s opulent image has become an increasingly difficult task for the Emirati government.

Dubai is currently thriving. Its economic growth outpaces similar nations in the Gulf due to the apparent success of its diversification efforts, with Dubai seemingly able to survive a post-oil world. Dubai, however, is still subject to the whims of the outside world, from its lack of monetary sovereignty and dependence on foreign investment. The 2009 debt crisis shows that the image carefully cultivated by Dubai’s government hides many economic and social risks lurking beneath Dubai’s skyscrapers.

One unsustainable social and ethical aspect of Dubai is the mistreatment of migrant workers. Let’s first consider the demographics of the UAE’s workforce. Similar to the makeup of other Gulf countries, there is a noticeable imbalance between nationals and foreigners in the labour force. The Gulf Research Centre reports that foreign workers dominate the workforce at every occupational level, with non-Emiratis making up almost 96% of the entire workforce.

This statistic solidifies that the country is undoubtedly heavily reliant on foreign labour. Nowhere else is this statistic more apparent than in Dubai, where in 2021, expatriates made up 75% of the Emirate’s population. While it is unclear whether a labour force dominated by migrants is sustainable, unethical treatment of any population of workers (regardless of their nationality) is absolutely unsustainable.

Countless examples of the mistreatment of migrant workers within Dubai have been provided by the media. One such situation that especially affects many unskilled migrants is the poor living conditions. Many underskilled migrants have little choice in terms of their accommodation. In most cases, migrant workers are forced into shared, cramped, and unhygienic living spaces, as displayed below.

Source: The Economist

Studies have shown that such forms of accommodation can impact mental health, while others have associated the decreased quality of temporary migrant accommodation with decreased life satisfaction for the migrants living there. In addition, these conditions were the perfect environment for COVID-19 to spread, implicitly jeopardising the Emirate’s efforts to quarantine the virus in earlier years.

Besides their abysmal living conditions, the restrictive labour governance system – more formally known as the Kafala System – which permeates the societies of many Gulf countries makes the lives of migrant workers within Dubai even more difficult. Firstly, Emirati citizenship is exclusively for those whose ancestors come from the 7 Emirates, and there is no naturalisation or permanent residency program. This means that migrant workers are not entitled to any public health assistance or work coverage if they develop work-related injuries. This is the case since most migrant workers end up in blue-collar jobs such as construction, where they are often deprived of cold water or shaded resting areas in the desert sun. Instead, it is often the case that the migrant worker sponsors will include health insurance as part of a worker’s contract. However, there have been cases where the insurance was insufficient to cover the full fees, resulting in further disparity through deductions of their already dirt-poor wages and worsening their already bad living conditions. On a further note, it is a commonality under the Kafala system for foreign labourers to have their passports confiscated to be used for processing a work visa. Oftentimes, this becomes another example of exploitation where some sources report that employers will retain their passports, making it difficult to escape an abusive employer.

There are 2 examples of irony contrasting the Gulf Tiger’s glamour and haze with its mistreatment of migrant workers. The first is that though the government was able to spend millions on massive skyscrapers and architectural wonders for tourists to view, seemingly nothing could be spared for the living conditions of migrant workers who likely laboured for months in strenuous conditions to build it in the first place. Furthermore, despite having the advantage of being a hot spot for expatriate workers with increasing numbers of people relocating to Dubai, it fails to sustainably facilitate this trend, with many disadvantaged migrant workers having little to no legal or financial protection against subpar work contracts.

What is certain for the Gulf Tiger is if it wishes to sustainably and ethically utilise its foreigner-dominant labour force, it must consider reformations to labour governance and better facilitate the rights and living conditions of migrant workers who are poorer and more susceptible to being taken advantage of.

As Dubai’s skyline continues to reach new heights, so do concerns about the city’s sustainability and environmental impact.

Dubai is home to the largest and most recognizable land reclamation projects in the world – most notably: the World Islands, Palm Jumeirah, and the iconic Burj Al Arab. These projects were designed to expand Dubai’s coastline and attract foreign investors, tourists, and social media attention. However, the construction of these artificial islands has taken a toll on marine life and biodiversity in the UAE. Despite being surrounded by desert, Dubai used marine sand, which provides a more stable foundation, for construction. This choice ultimately resulted in detrimental consequences as Dubai is expected to lose 10,000 to 15,000 cubic metres of beach sand annually. The construction of Palm Jumeirah has disrupted wind patterns, accelerating erosion and causing marine sediment to shift 40 kilometres in just five years. Moreover, the World Islands are at risk of sinking as the sand that was extracted from the seabed to build it is gradually returning to its place of origin, pushing construction companies to re-extract the sand from seabeds. All the movement caused during construction has clouded the water with silt, stifling the once-thriving marine biodiversity; oyster beds are buried under up to two inches of sediment, causing irreparable damage to coral on the seafloor.

Dubai’s reliance on the Jebel Ali Power and Desalination Complex, the world’s largest facility of its kind, highlights its heavy dependence on fossil fuels. The Complex supplies the city with water by extracting and treating seawater through its 43 desalination plants. Given its desert surroundings, Dubai’s water consumption levels are remarkably high, with an average water consumption of 550 litres per person. This level of water consumption poses significant risks to food security and economic stability, as by 2050, the entire Gulf region could face a 50% reduction in water availability per capita. The escalating demand for water through desalination is likely to boost the United Arab Emirates’ already high carbon emissions, which surpassed 200 million tons in 2022, ranking among the world’s highest per capita.

Furthermore, the construction of Dubai’s artificial islands exacerbates the strain on the Gulf’s resources. The average temperature around Palm Jumeirah increased by roughly 13 degrees over 19 years. Land reclamation for these projects, combined with the discharge of brine and industrial waste, has led to the proliferation of harmful algae blooms or red tides in the Persian Gulf. This poses a health risk to both workers and the general population as these blooms release toxins that lead to illnesses ranging from gastrointestinal issues to respiratory problems. Seagrass meadows in the area are also struggling, causing a decline in the nursing grounds for commercially valuable species like pearl oysters, leading to a strain on tourism, fisheries, and other sectors dependent on a healthy marine environment. Some of these harmful blooms have forced desalination plants to reduce or shut down operations. This is particularly concerning given Dubai’s heavy reliance on desalinated drinking water.

Source: NASA: Before and after flooding

Despite the UAE being an extremely arid country, flash floods have become another major concern. Recent heavy rainfall, equivalent to a year’s worth, plunged Dubai underwater. Dubai, being heavily urbanised, leaves little green space to absorb moisture, and drainage facilities were unable to withstand the high levels of rainfall. In addition to flash floods, the city frequently experiences sandstorms which pose a serious health risk to residents. These can lead to severe respiratory infections and health problems while also damaging buildings and machinery. Both the storms and floods disrupt air traffic, forcing flight diversions, delays, and cancellations. These climate-related disasters further emphasise Dubai’s weak infrastructure, ill-equipped to withstand the effects of climate change, raising questions about its preparedness for future challenges.

Dubai has taken steps to address the damage through environmental initiatives and new technology, but the pressure is building to do more. Last year, the city hosted the United Nations global climate summit, known as COP 28, where environmental and sustainability concerns took centre stage. COP 28 ended with the first-ever call to move away from fossil fuels. The summit saw a landmark agreement to support vulnerable nations facing the worst of climate change’s impacts. A closely watched area in Dubai was carbon markets, though no agreement was reached, it is expected that key questions related to these will be addressed in COP 29. Despite facilitating important progress, COP28 fell short of delivering decisive actions on climate change that science says are of paramount importance.

In summary, what can we expect for the future sustainability of the Gulf Tiger? Given forecasts on declining demand for fossil fuels, the need for a more effective economic model to diversify the city’s income becomes increasingly prominent as economic sustainability becomes a race against time. Furthermore, if the Emirate wishes to sustainably foster a growing expatriate population, it must address its flawed immigration system and social disadvantages experienced by poorer migrant workers. Moreover, if Dubai hopes to fully address contemporary environmental issues, such as the fight against climate change, it must look to alternative ways of attracting foreign investment that do not cause negative externalities and accelerate its efforts in the shift from fossil fuels. If the city of Dubai wishes to fully capitalise on the extraordinary momentum it has gained in the past and solidify itself as a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable empire, it must sustainably develop or risk fading away as quickly as it rose.

References

Al-Otaibi, G. (2015, March 19). By the numbers: Facts about water crisis in the Arab World. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/arabvoices/numbers-facts-about-water-crisis-arab-world

Amazing Dubai. (n.d.). Dubai History: from the desert to the city of future

Amazing-Dubai.com. Amazing Dubai. https://amazing-dubai.com/history-of-dubai.html.

Amnesty International. (2023, December 15). CLIMATE JUSTICE GLOBAL GLOBAL: WHAT HAPPENED AT COP28? ESSENTIAL NEED-TO-KNOWS. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org.au/global-what-happened-at-cop28-essential-need-to-knows/?cn=trd&mc=click&pli=23501504&PluID=0&ord=%7Btimestamp%7D&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwz42xBhB9EiwA48pT78SiKQbdhClsgb9FRZQ-J5E46YbFIWK9Yu0pgwGrqDN8zqs6XWY27xoCLSsQAvD_BwE

Azhar, S. (2019, March 27). Dubai economic growth at its slowest since 2009 debt crisis. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1R80RN/#:~:text=Dubai%20needed%20a%20%2420%20billion,billions%20of%20dollars%20of%20debt

Bash, C., Bresniker, K., Faraboschi, P., Jarnigan, T., Milojicic, D., & Wood, P. (2024). Ethics in Sustainability. IEEE Design & Test, Design & Test, IEEE, IEEE Des. Test, 41(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1109/MDAT.2023.3283351

BP. (2023, January 30). Oil demand falls over the outlook as use in road transportation declines. BP. https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/energy-outlook/oil.html

Burbano, L. (2021, July 23). What happened to Dubai man-made islands? – Tomorrow.City – The biggest platform about urban innovation. Tomorrow.City. https://www.tomorrow.city/dubai-man-made-islands/

Butler, T., & Butler, R. (2005, August 23). Dubai’s artificial islands have high environmental cost. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2005/08/dubais-artificial-islands-have-high-environmental-cost/

Cassidy, E. (2024, April 19). Deluge in the United Arab Emirates. NASA Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/152703/deluge-in-the-united-arab-emirates

DE BEL-AIR, F. (2015, July). Demography, Migration, and the Labour Market in the UAE. Migration Policy Centre.

https://hdl.handle.net/1814/36375

DeMont Institute of Management & Technology. (2023, May 15). Why are increasing numbers of people relocating to Dubai?.

https://www.demont.ac.ae/blogs/why-more-people-are-relocating-to-dubai/

Frommers. (2015). History in Dubai | Frommer’s. Frommer’s Travel Guides. https://www.frommers.com/destinations/dubai/in-depth/history

Gani, M. S. (2018, March 13). Pros and cons of dirham’s peg to the dollar. Gulfnews. https://gulfnews.com/business/analysis/pros-and-cons-of-dirhams-peg-to-the-dollar-1.1493644

Hassan. R. (2018, April 24). The UAE’s Unsustainable Nation Building. Yale University.

https://archive-yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/uaes-unsustainable-nation-building

Human Rights Watch. (2023, December 3). Questions and Answers: Migrant Worker Abuses in the UAE and COP28. Human Rights Watch.

https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/12/03/questions-and-answers-migrant-worker-abuses-uae-and-cop28#Q3

Human Rights Watch. (2022, June 5). UAE: Sweeping Legal ‘Reforms’ Deepen Repression.

Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/06/05/uae-sweeping-legal-reforms-deepen-repression

IEA. (n.d.). Growth in global oil demand is set to slow significantly by 2028. International Energy Agency.

https://iea.org/news/growth-in-global-oil-demand-is-set-to-slow-significantly-by-2028.

Kadıoğlu. U. (2022). Taken Hostage in the UAE. Harvard International Review.

https://hir.harvard.edu/taken-hostage-in-the-uae/

McQue. K. (2020). This article is more than 3 years old ‘I am starving’: the migrant workers abandoned by Dubai employers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/sep/03/i-am-starving-the-migrant-workers-abandoned-by-dubai-employers

MIGRANT-RIGHTS. (2023, September 21). Comparison of Health Care Coverage for Migrant

Workers in the GCC. MIGRANT-RIGHTS.

Mishrif, A. & Kapetanovic, H. (2018, January). Dubai’s Model of Economic Diversification. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322336014_Dubai%27s_Model_of_Economic_Diversification

Oanda. (n.d.). Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham Currency. Oanda. https://www.oanda.com/currency-converter/en/currencies/majors/aed/#:~:text=The%20United%20Arab%20Emirates%20dirham%20is%20pegged%20to%20the%20US,of%201%20USD%20%3D%203.6725%20AED.&text=The%20United%20Arab%20Emirates%20

Olafsson, H. (2022, February). Assessment of Palm Jumeirah Island’s Construction Effects on the Surrounding Water Quality and Surface Temperatures during 2001–2020. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358695726_Assessment_of_Palm_Jumeirah_Island%27s_Construction_Effects_on_the_Surrounding_Water_Quality_and_Surface_Temperatures_during_2001-2020

Paul, A. (2024, January 12). Dubai’s Costly Water World. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/18/business/dubai-water-desalination.html

Reber, L. (2021). The cramped and crowded room: The search for a sense of belonging and emotional well-being among temporary low-wage migrant workers. Emotion, Space & Society, 40, N.PAG. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100808

Reuters. (2023, July 6.). UAE attracts record $23 billion in foreign investment in 2022, UN report says. Reuters. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/items/7547a60d-a78d-42fe-a389-f90601f297ee

Salahuddin, B. (2006). The Marine Environmental Impacts of Artificial Island Construction Dubai, UAE. DukeSpace. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/items/7547a60d-a78d-42fe-a389-f90601f297ee

Sawe, B. E. (2019, November 8). What Are The Sources Of Drinking Water In Dubai? World Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-are-the-sources-of-drinking-water-in-dubai.html

Teaching Abroad Direct. (2023). Living and Working in Dubai Statistics 2023. Teaching Abroad Direct.

https://www.teachingabroaddirect.co.uk/blog/living-and-working-in-dubai-statistics

Teather, D. (2009, November 29). Recession and debt dissolve Dubai’s mirage in the desert.

The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/nov/29/dubai-financial-crisis

The Economist. (2020, April 23). Migrant workers in cramped Gulf dorms fear infection. The Economist.

Uppal, R. (2023, July 20). UAE’s Abu Dhabi sees strong industrial sector growth amid diversification push. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/uaes-abu-dhabi-sees-strong-industrial-sector-growth-amid-diversification-push-2023-07-19/

Uppal, R. & Al Sayegh, H. (2024, February 24). UAE dropped from financial crime watch list in win for nation. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/fatf-financial-crime-watchdog-removes-uae-gibraltar-grey-list-2024-02-23/

Vittori, J. & Page, M. T. (2020, July 7). Dubai’s Role in Facilitating Corruption and Global Illicit Financial Flows. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/07/07/challenges-and-recommendations-pub-82190#:~:text=bill%20of%20health.-,The%20foremost%20obstacle%20to%20reducing%20Dubai%27s%20problematic%20role%20is%20its,it%20has%20never%20completely%20recovered.

Warner, K. (2023, March 23). Dubai commits $1bn to tech start-ups amid global sector volatility. The National News. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/2023/03/22/dubai-commits-1bn-to-tech-start-ups-amid-global-sector-volatility/

Walther, L., Fuchs, L. M., Schupp, J., & von Scheve, C. (2020). Living Conditions and the Mental Health and Well-being of Refugees : Evidence from a Large-Scale German Survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(5), 903–913.

Winkler, M. A. (2018, January 13). Dubai’s the Very Model of a Modern Mideast Economy. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-01-14/dubai-s-the-very-model-of-a-modern-mideast-economy

Wintermeyer, L. (2023, June 16). Dubai: On The Road To Becoming A Top Global Financial Services Hub. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lawrencewintermeyer/2023/06/16/dubai-on-the-road-to-becoming-a-top-global-financial-services-hub/?sh=635ada775a9c

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.