Envision a world in which one’s prosperity spills over to enhance the lives of numerous individuals – a utopian paradise where the rich get richer while concurrently improving the living standards of the working class. Such was the fragile promise of Trickle-Down economics, an approach that sought to bridge vast income inequalities while also stimulating job creation and fostering economic growth. Trickle-down economics presented itself as an umbrella solution – targeting and resolving a multitude of economic issues and as “a rising tide that will lift all boats…accelerating economic growth, creating more jobs and rising income, but not uniformly”.

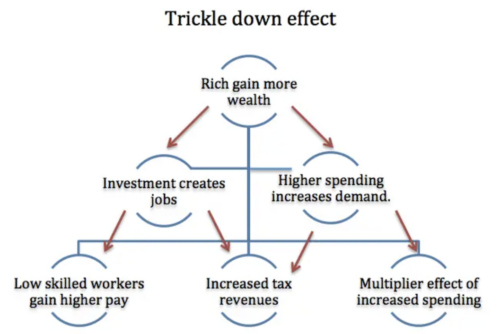

Put simply, the theory of Trickle-Down economics explores how tax breaks for high-income earners result in multiplied expansions, increased job creation, narrowed income inequalities, and a strengthened government budget.

Tax breaks help high-income-earning individuals and firms retain a greater proportion of their disposable income. Subsequently, fuelled by an increased affinity to consume within the domestic economy, the overall derived demand for labour in the manufacture and production of domestic goods is expected to rise. This increased spending in the economy eventually “trickles down” to the working-class populations, thereby promoting both economic growth and a narrowing of income inequalities. Additionally, corporate tax cuts further improve after-tax rates of return on investment, which in turn may stimulate higher levels of investment within economies.

In theory, the trickle-down effect may potentially generate multiplied injections into the economy through greater job creation and increased domestic consumption and investment.

Figure 1: Economics Help, 2022 Describing the basic theory of trickle-down economics.

While the theory of “Trickle-Down Economics” only gained more recognition in the 1970s-80s, the concept of a downward, vertical flow of economic benefits stemming from the growing prosperity of the wealthy has persisted over many years. Jawaharlal Nehru, a former Prime Minister of India and an anti-colonial nationalist first, discussed the idea of a “trickle-down” during the 1930s in his paper on Hobson-Lenin’s theory of imperialism, identifying that the “exploitation of India… brought so much wealth to England that some of it trickled down to the working class and their standard of living”.

The predominant factor facilitating the success of the trickle-down stems from the tax breaks granted to the wealthiest corporations and individuals.

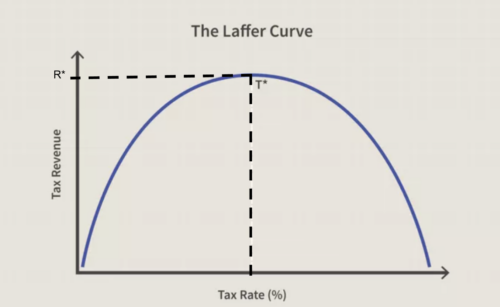

The Laffer Curve, constructed by supply-side economist Arthur Laffer, presents a rough visualisation of the relationship between an economy’s tax rates and government tax revenue. As displayed in Figure 2, a proposed reduction in tax rates would typically result in a fall in government tax revenue.

The trickle-down theory suggests that this fall will be compensated through the theorised boosts in domestic consumption, investment and job creation. Tax revenue is thereby expected to rise significantly, allowing the government to channel revenues into public programmes and infrastructure in the economy. Therefore, a country may experience multiplied expansions in terms of growth and narrowing income inequalities – allowing its population better access to improved living standards while also strengthening the government budget.

Figure 2: Investopedia, 2023 The Laffer Curve

However, the integral assumption that forms the backbone of this theory conversely presents its inherent contradictions. The idea of lowering marginal tax rates to promote greater domestic consumption and investment is rarely true, as oftentimes, tax breaks generate additional tax savings, “which have been largely stashed in financial markets instead of being reinvested in ways that stimulate growth and employment”. Consequently, as financial investments are largely unproductive, the primary driver of the trickle-down theory proves to be lacking. Therefore, the collapse of the idea of wealthy individuals and corporations reinvesting tax savings may both worsen the government budget and have insignificant impacts on economic growth and job creation.

Furthermore, another contradictory assumption arises as the theory also fails to account for the regressive nature of cutting taxes only for wealthy members of society. As a consequence of constructing a tax system more “skewed towards the wealthy”, – high-income earners are subject to lower levels of tax, whereas “low-income earners receive nothing”. Moreover, as tax cuts weaken the government’s budget, the economy may be unable to fund public welfare programs. This, coupled with the previously discussed lack of investments and domestic consumption, may exacerbate income inequalities.

Additionally, excessive tax cuts to the rich may, in fact, result in increased aggressive bargaining as “high-income earners aim to increase their own compensation”. The underlying assumption that higher tax savings promote greater incentives to increase wages and improve productivity by reinvesting in research and development is further contradicted, as greater tax savings may give rise to “greedy” self-serving behaviours. Wealthy companies reflect a tendency to prioritise the absorption of such tax savings – choosing to channel money towards paying bonuses to executives, buying back stocks and investing in unproductive financial markets.

Following the stock market crash in October 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression, Hoover’s approach to economic recovery consisted of managing corporations and industry: “encouraging business leaders to keep workers,” hence minimising layoffs, while also “maintaining current wage rates” despite the weak state of the economy.

Hoover believed that by maintaining wages and minimising layoffs, the vertical flow would eventually carry down the prosperity of businesses to the average person. However, this was undercut by Hoover’s own excessive meddling in the economy.

Unfortunately, his plan failed as industrial goods prices in the domestic economy fell over the 1930s.

Hoover’s objectives of maintaining a stable government budget coupled with incentives to protect the farming industry drove him to sign the “Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act”, – causing the imposition of tariffs of up to 40% on over 900 imported goods. This inadvertently resulted in a trade war as other countries retaliated by imposing similar tariffs on American exports, ultimately resulting in an economy-wide deflation as the nation’s gross domestic product fell 8.5% and unemployment rates rose to 8.7%. With a mass decline in exports coupled with crippling deflation, Hoover’s plans ultimately failed, resulting in soaring unemployment levels of up to 23.6% in 1932.

Additionally, Hoover intended to aid economic recovery through excessive government spending on projects such as the construction of the Hoover Dam and the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Furthermore, Hoover believed that a strong government budget would restore public confidence, driving him to catastrophically raise taxes for high-income earners from 25% to 63%. This worsened the Depression immensely.

Hoover’s inability to allow the free market to “heal itself” ultimately magnified the economic downturn.

The trickle-down theory is vital to Hoover’s economic approach because of its absence and inhibition. Hoover’s decision to increase taxes on high-income earners during a period when tax cuts would have been well warranted ultimately hindered the possibility of potential trickle-downs leading to economic recovery and job creation.

While it is impossible to assume that the trickle-down effects would have resolved the Great Depression – especially with low levels of confidence hindering the affinity for corporations and high-income earners to consume or invest during this period – it is undoubtedly apparent that a cut in taxes would have eventually driven the economy into a better state: allowing the country to recover within a couple of hard years as opposed to being plunged into a decade long disaster.

Reaganism or Reaganomics is another instance in which the trickle-down theory takes prevalence—only this time, unlike Hoover, Ronald Reagan attempted to target and exploit economic growth by focusing his policies on those at “the top of the food chain,” granting tax breaks and other economic benefits to wealthy individuals and corporations. Reagan ultimately trusted the process of the vertical flow to carry down the prosperity faced by high-income earners and increase opportunities for lower-income workers.

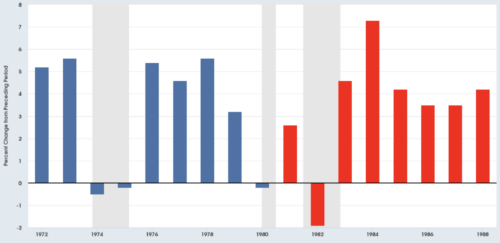

Upon cutting taxes from 70% to 50% (1981) and later to 28% (1986), “real GDP growth averaged 3.5%, compared to 2.9% in the preceding eight years, and the annual average unemployment rate declined by 1.7 percentage points”.

Figure 3: FRED: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2018. Annual percentage change in real GDP 1972-1988 (Reagan years: red)

However, the extent of success of the trickle-down approach, coupled with Regan’s policies aimed at decreasing spending on domestic social programs, is often debated in terms of a weakened government budget, rising income inequalities and its contributions to increased inflationary pressures. The success of the trickle-down approach was further questioned as surging growth rates may have been fuelled by “low interest rates and humongous government spending”.

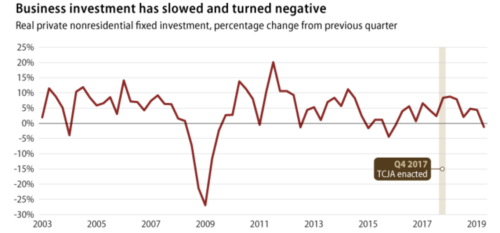

In more recent history, evidence of trickle-down economics is still apparent. In 2017, Donald Trump cut corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%, promising that the U.S.’s average household income would increase by up to $4,000. This promise was, however, left unfulfilled as the trickle-down process, which aimed to translate greater corporate tax savings into higher wages for workers, never materialised. The promised booms in investments failed to come to fruition for a multitude of reasons – including the fact that “effective tax rates on U.S. corporate investment… were already quite low”, highlighting the insignificance of corporate tax cuts on levels of investment. Trump’s “erratic pronouncements on tariffs” seemingly caused uncertainty – resulting in falling investments, directly contrasting Trump’s promises following the 2017 tax cuts.

Figure 4: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2019 fall in investments following the TCJA enactment.

Overall, the highly controversial debate surrounding the trickle-down economic theory persists due to its ineffectiveness – stemming from its constant inability to deliver on its promises and its potential to satisfy the interests of the “politically powerful [and] moneyed”. Despite appearing to be an umbrella solution addressing and achieving fiscal stability, narrowed income inequalities, economic growth and increased employment, the trickle-down theory is often criticised due to its counterproductive nature. As the discourse continues, it is imperative to critically examine the assumptions, implications and underlying contradictions of the trickle-down theory, especially considering their potential to perpetuate social and economic disparities.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.