It’s 2024, and the US economy is back. After COVID, it experienced an inflation surge far beyond what many had seen in their lifetimes. However, inflation peaked back in 2022, and has since declined, while GDP continues to grow and unemployment remains historically low. Against the predictions of economist after economist, a recession in 2023 never came to be (Smith & Gilbert, 2022). Despite this, Americans still see an economy in poor shape. What gives?

The vibecession (a blend of the words ‘vibes’ and ‘recession’) describes the disconnect between the state of the economy and the public’s perception of it. This term came into recent prominence to characterise the economic situation in the United States. Throughout 2023, as inflation continued to moderate towards the Fed’s 2% target and unemployment remained below 4%, telling signs of a resilient labour market, consumers continued to feel dour about the economy (Schneider & Saphir, 2024). In February 2024, 26% of registered voters said that the U.S economy was ‘good’ or ‘excellent’, while a majority (51%) believed current economic conditions were poor (Casselman et al., 2024).

However, with consumer sentiment rising to its highest level last seen since July 2021, some economists and commentators have dubbed the vibecession to be nearing an end (Golle, 2024). This provides a timely opportunity to look back and gauge what factors were behind the disconnect between the economy and consumer sentiment, and what implications might there be for policymakers in the US as well as here in Australia. Here are three theories to explain the vibecession:

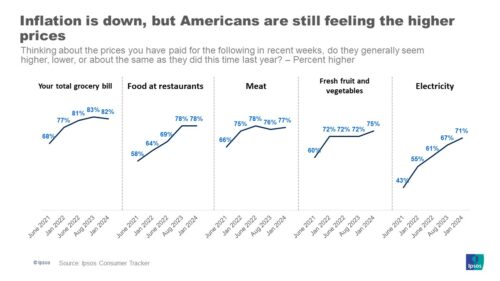

The simplest explanation is that consumer sentiment is a lagging indicator of the economy and that inflation expectations can be sticky. While economists and policymakers may point to declining inflation from a period of high price levels as a sign of good economic health, it’s still no help to consumers who are continuing to feel the effects of price rises. The important point of note here is that even as inflation comes down, prices are still rising, albeit at a lower rate. Prices are still higher than what it was 2 to 3 years ago, and this means that when consumers do their shopping at the grocery, or pay for their electricity bill, or eat out, they are going to notice that prices are higher than what it used to be (Yound & Mendez, 2024).

Source: Ipsos Consumer Tracker

This is especially true for ‘sticky’ goods or services, product pricing that is resistant to changing market conditions, such as groceries or wages. When the prices of these sticky-down goods and services increase, owing to market factors such as supply chain disruptions and labour shortages, it cannot move down as easily as it did going up (Battarai & Stein, 2024). This means that consumers will continue to feel the effects of elevated prices for some time, until they are able to adjust to these new prices. How long that will take will depend on how quickly real wages grow, but the dissatisfaction with prices is reflected in the pessimism of consumer sentiment. In addtion, a widespread lack of affordable housing and growing inequalities in measures of wellbeing such as life expectancy and level of education, may speak to dissatisfaction with the economy on a more structural level (Ip, 2023).

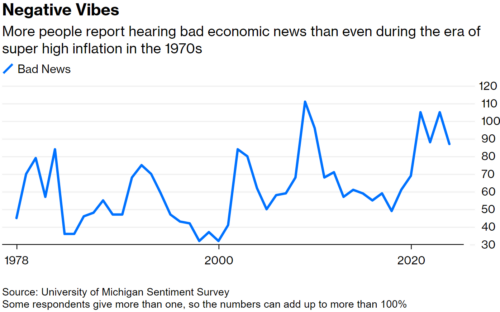

One explanation that has been proposed is the influence of the media in creating a negative economic narrative. If the public is constantly hearing about how dire the economic situation is in terms of housing, climate change and healthcare, then surely this would lead many to believe that the economy is troubled, and consequently how this would impact their financial situation (Sahm, 2023). Similarly, when there are widespread reports of economists projecting a recession with high certainty, that’s bound to have an impact on the confidence of consumers.

Source: University of Michigan Sentiment Survey, Bloomberg

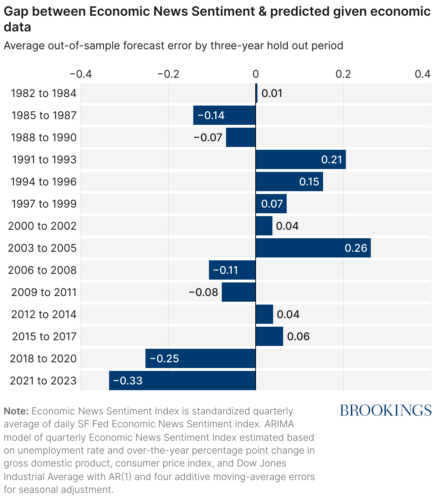

This theory was lent credence by the Brookings Institution, which found that the media has been increasingly negative about the economy than what the fundamental economic data would have suggested (Galston & Daniel S. Hamilton, 2024). It determined that between 2018 and 2020, the tone of economic news coverage was more negative than predicted, deviating from the usual gap between economic news sentiment and predicted given economic data from 2006 and 2017. This difference was exacerbated between 2021 and 2023, when the tone became even more negative. Combined with the cascading series of news and events now at our fingertips thanks to social media and the 24 hour news cycle, crisis fatigue could also be a potent factor in diminishing consumer optimism (Rozelle-Stone, 2022). Altogther, this may go some way to explaining how pessimistic consumers feel about the economy despite its surprising resilience.

Source: The Brookings Institution

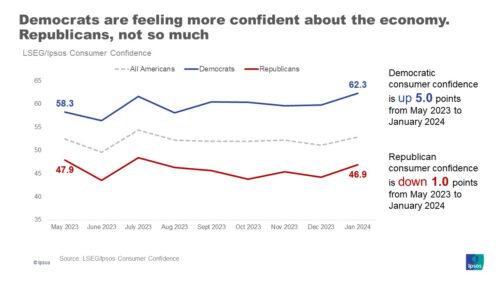

In a society as polarised as the United States, where people are divided and sorted into political faultlines, even banal economic measures and metrics can be influenced by political realities. While overall consumer confidence is broadly low, there’s a wide gulf between how people of different political leanings feel about the economy, which speaks to how the economy is oftentimes inextricably linked to politics . Consider the graph below which shows consumer confidence between Democrats and Republicans, illustrating how Democrats see an improving economy, as compared to Republicans who see one that’s still struggling (Yound & Mendez, 2024).

Source: London Stock Exchange Group/Ipsos Consumer Confidence Index

This partisan divide in consumer sentiment may speak to the increasingly siloed media ecosystem that people source their news from, whereby one point of view is likely to be much more prevalent than the other. Increased consumption of ideologically biassed news sources may result in what economists have coined ‘asymmetric amplification’, where one side is likely to view the economy in a much more gloomy perspective when the other side is in charge, and vice versa (Cummings & Mahoney, 2023).

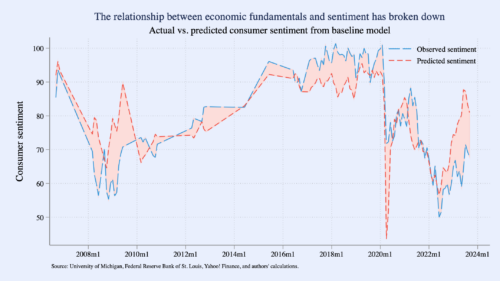

Much like the tone of economic news diverging from predicted trends in recent years, so too has consumer sentiment strayed away from what the fundamentals would lead us to believe. Statistical models used to predict consumer sentiment pre-pandemic have broken down since the turn of the decade, with former White House economists Ryan Cummings and Neale Mahoney observing that predicted consumer sentiment should be as much as 13 points higher than the actual value. While sentiment among Republicans have become more sensitive to the politics of the day (i.e. the party in command of the presidency at the time), this only explains around 30% of the difference between actual and predicted sentiment. This leaves plenty of room for other factors, such as the aforementioned ones discussed above.

Source: University of Michigan, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Briefing Book

Given these explanations, questions remain as to how policymakers should respond to gloomy consumer sentiment when the economic metrics are pointing towards the other direction. If people are worried about their finances and the state of the economy despite the contrary, should that really concern the government of the day?

Economists will say that actions speak louder than words, as spending and hiring continues to be strong. Eventually, real wages will catch up and people’s price expectations will adapt, allowing consumer confidence to rebound. This is may very well be true in the US, where consumers may finally be seeing the light at the end of the tunnel (Krugman, 2024).

What may concern policymakers most is whether this doom and gloom will translate into their perception of how the economy is managed, and by extension, the approval of their leaders. Come November, US President Joe Biden will certainly be hoping that Americans are feeling optimistic enough about the economy to credit him with a second term. Here in Australia, the Albanese government is counting its stars for when the Reserve Bank begins cutting interest rates as many economists have predicted, signalling to gloomy Australians that the worst of times have passed and relief is on the way (Hassan & Nguyen, 2024).

Ultimately, the vibecession may well be the precursor to how consumers respond to difficult economic conditions going forward. In a partisan world fueled by crisis fatigue and a negative media ecosystem, bad vibes may just be the new normal.

References

Battarai, A., & Stein, J. (2024, February 2). Inflation has fallen. Why are groceries still so expensive? The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/02/02/grocery-price-inflation-biden/

Casselman, B., Depillis, L., & Zhang, C. (2024, March 5). Brighter economic mood isn’t translating into support for Biden. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/05/business/economy/biden-economy-times-siena-poll.html

Cummings, R., & Mahoney, N. (2023, November 13). Asymmetric amplification and the consumer sentiment gap. Briefing Book. https://www.briefingbook.info/p/asymmetric-amplification-and-the

Galston, W. A., & Daniel S. Hamilton, J. P. Q. (2024, January 31). Why are Americans so displeased with the economy?. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-are-americans-so-displeased-with-the-economy/

Golle, V. (2024, March 28). US consumer sentiment jumps to highest level since July 2021. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-28/us-consumer-sentiment-jumps-to-highest-level-since-july-2021

Hassan, M., & Nguyen, V. (2024, March 26). Consumer sentiment dips as cost-of-living gloom continues. Melbourne Institute. https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/publications/macroeconomic-reports/latest-news/index-of-consumer-sentiment

Ip, G. (2023, November 15). While all inflation feels bad, housing inflation is the worst. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/economy/housing/while-all-inflation-feels-bad-housing-inflation-is-the-worst-f12f518d

Krugman, P. (2024, January 23). Is the vibecession finally coming to an end?. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/22/opinion/biden-trump-vibecession-economy.html

Rozelle-Stone, R. (2022, September 6). When tragedy becomes banal: Why news consumers experience crisis fatigue. The Conversation.

https://theconversation.com/when-tragedy-becomes-banal-why-news-consumers-experience-crisis-fatigue-187756

Sahm, C. (2023, October 30). Americans like sharing bad economic news way too much. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-10-30/americans-like-sharing-bad-economic-news-way-too-much?srnd=undefined

Schneider, H., & Saphir, A. (2024, March 21). Fed sees three rate cuts in 2024 but a more shallow easing path. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/feds-rate-cut-confidence-likely-shaken-not-yet-broken-by-inflation-2024-03-20/

Smith, C., & Gilbert, C. (2022, December 7). US unemployment rate set to surpass 5.5%, economists predict. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/c2d4d4b5-cbc8-4b5c-9ea3-44e9742d5b3a

Yound, C., & Mendez, B. (2024, February 9). Why are Americans still so pessimistic about the economy? Ipsos. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/why-are-americans-still-so-pessimistic-about-economy

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.