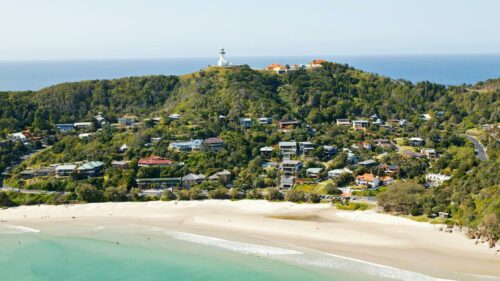

Byron Bay, where 17.6% of the housing stock is listed on Airbnb (Image Source: Kayak)

When Airbnb first arrived in Australia in 2012, the nation was experiencing a housing construction boom, especially in new apartments, and rent was growing at a slow pace. A decade later, we are in the middle of a rental crisis, and while housing affordability has always been a complex subject, attention has been inevitably pointed to the cannibalisation of the housing supply by Airbnb and other short-term rentals (STRs). There exist two mechanisms which illustrate the relationship between short-stay rentals and long-term rental units. The effects of this relationship create a substantial problem for the supply of rentals especially in holiday areas, but with the ubiquity of STRs, locals in metropolitan areas too are facing the negative consequences. This poses a question for the future as to what solutions can we offer to alleviate the pressure home and rental buyers are currently facing.

The relationship between STRs and the housing market is definitely one which exacerbates housing crises. We can first observe this through housing markets in other regions across the world. To be simplistic, there are two types of people to consider here – tourists who desire STRs, and renters who desire rental properties. Furthermore, there are two mechanisms by which STRs and Airbnb operate to disrupt the market. The first mechanism is a conversion mechanism. Essentially, when a housing unit is converted into an Airbnb, it loses its status as a potential rental property, thus decreasing the overall supply in the rental market. By economic intuition, this pushes the prices of rental units up and reduces the number of renters who are willing and able to purchase a rental unit at that price. Ironically, the original purpose of Airbnb was not to turn homes into hotels, but rather allow those travelling on a lower budget to find hosts to stay with – a model that would not have taken entire properties off the rental market. Nowadays, 85% of properties on Airbnb in Australia are entire properties.

But it’s the second mechanism that explains why Airbnb has been cannibalising the rental market at rapid pace – the name given to it is ‘hotelization’. From the perspective of an Airbnb property owner, as long as they keep their prices below the price of a hotel room, but still earn a substantial premium over the kind of returns a rental property might offer, then there is an incentive to make them significantly more expensive than rental properties. This price difference is illustrated further when comparing the average prices of rental properties and STRs. In 2022, the average weekly rent in Greater Melbourne is $491, while average STR rate is $253 per day, equating to $1,771 per week. This statistic illustrates the opportunity cost for rental leaseholders. In continuing to rent out to long-term residents, they miss out on potentially gaining much higher returns in the market for Airbnbs – even if the occupancy rate is as low as 30% – and thus are incentivised to convert their rental properties to Airbnbs and further strains the supply of rental units. Through the two mechanisms we’ve discussed, the economic sense underlying the Airbnb boom is difficult to argue with. So how has this translated to the situation we face now in Australia?

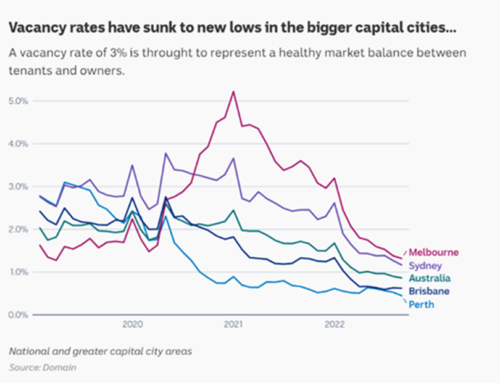

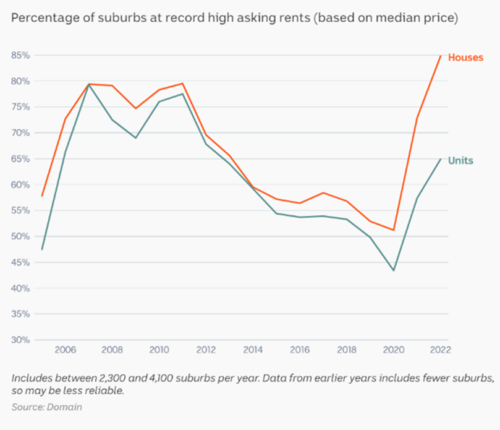

Although short-term rentals are not the sole contributor to the lack of housing supply in Australia, they still prove to be a considerable stakeholder in the availability of rentals. Since the ending of COVID restrictions, the impact of short-term rentals on the market was exacerbated by borders opening and international students being welcomed and looking for a place to stay. As COVID struck, vacancy rates across cities experienced an increase as the stoppage in tourism caused short-stay listings to convert to longer term rentals, especially in Melbourne where vacancies peaked at more than 5% in 2021. However, the number of available tenancies started to drop post-COVID as short-stay properties snuck into the market, coinciding with travel restrictions fading and tourism becoming more accessible again. This was especially obvious in areas along the coast such as Byron Bay where almost half of the town’s rental accommodation was listed on Airbnb, constituting 17.6% of the entire housing stock as of July 2022. Although short-term rentals accounted for 2% of overall housing stock across the country, holiday areas are substantially affected by this contraction of supply in tenancies.

(Source: ABC)

(Source: ABC)

Within metropolitan areas, the reduction in supply still impacts those looking to rent locally. Australia already has fewer homes per 1000 people than the average among developed nations according to the OECD, so every home counts in putting a roof over everyone’s head. In Melbourne and Sydney alone, there are 20,768 and 22,659 Airbnb listings respectively, preventing tens of thousands of tenants from finding a home. A study by the University of Sydney found that in Hobart, 47% of properties on Airbnb had previously been long-term rentals at some point. Furthermore, just a few properties can move the needle significantly, with the study finding that converting just 195 houses to short-term rentals can halve the vacancy rate from an already less-than-ideal 2% to a dangerous 1%. For some, the market has changed completely where working couples and professionals are struggling to secure a lease, not to mention others who are in less secure financial positions. Without overshooting the asking price by miles or offering months of rent in advance, it has become increasingly difficult to secure a tenancy. With an increasingly large number of suburbs at record high asking rents, affordability has plummeted with the constriction of supply in housing available with the private rental market holding onto these properties. Whilst short-stay listings are only one of many factors alongside the ratio of public housing and overarching economic conditions such as rising interest rates, any action towards its regulation or overturn to this ‘landlord’s market’ to favour tenants can help in combating the rental crisis.

(Source: ABC)

The crisis in housing affordability and supply has fuelled calls for government intervention within the industry. Aside from increasing supply broadly, commentators and policymakers have identified the short-term rental market as a potential avenue where the power of regulation could work to flip as many short-stay rentals as possible into the long-term rental market, increasing supply and boosting affordability. Historically, Australia’s short-term rental regulations have been lenient compared to its overseas counterparts, so can strengthening these controls work to provide relief to prospective buyers and renters?

One idea that has been floated in response to this question are day-caps on rental properties, limiting accommodation providers on how many nights a year a host can rent out homes for short-stay. The hope is that by limiting the amount of nights a property can act as a short-term rental, the reduced financial viability of keeping the property up all year round will encourage owners to lease their property to the long-term rental market.

As for the effectiveness of day-caps, we can look to New South Wales for clues. In 2021, the then-Coalition state government introduced various reforms and policies aimed at increasing rental affordability. One of the key measures was a 180-day cap for non-hosted short-term rentals, which applied to the Greater Sydney Area as well as various regional councils across the state.

In the years that this policy has come into effect, there has yet to be any significant improvements made to rental affordability and supply. As demonstrated previously, not only have vacancy rates tightened, but rents continue to skyrocket and squeeze renters ever more so. While these changes cannot be fully attributed to the effectiveness of the state’s day-cap, some local council officials believe that the cap’s leniency has played a role in exacerbating the problem. The NSW Office of Fair Trading, responsible for enforcing the cap, has not issued any penalties since it has come into effect, despite receiving over 550 complaints.

However, the challenge of leniency in enforcement that many local councils have faced is not a universally shared experience overseas. When strong short-stay controls have been paired with effective enforcement, governments are able to reduce the number of short-stay listings and thus, increase supply within the long-term rental market. In Amsterdam, following the introduction of mandatory registrations of holiday rentals in 2021, Airbnb lost 80% of its housing stock in the city, releasing more than 13,000 properties that could now enter the ordinary rental market. This is enforced by financial penalties of up to €21,000 if landlords are found to be breaking the rules. Other cities such as Toronto and Boston also impose tourist taxes on short-term rentals to disincentive landlords from operating them and to encourage tourists to attend licensed, regulated hotels and resorts. In return, these taxes also provide revenues that could go into providing additional social and affordable housing, offsetting the loss of permanent long-term housing due to short-stay properties.

Amsterdam, where regulations have decreased Airbnb stock by 80% (Image source: Wikipedia)

As mentioned in the prior examples, many policies and changes have been introduced within Australia, but there is yet to be any standardised national approach which some are calling for. This is because planning, tenancy and rental reforms are typically addressed at the state and local level, meaning the actions taken to address this situation vary across the local and state level. However, the federal government has shown a recent willingness for further regulatory interventions in the short-term rental market, which may indicate a more coordinated and effective framework to respond to the challenge that we face in regards to short-stay rentals and the housing market.

In addition, the willingness of local councils and state governments to move further in curbing the proliferation of short-term rentals, either by further limiting the day-cap to 60 nights or by introducing annual registration fees, suggests that the current regulatory framework is not producing dividends for renters in regards to affordability and that there is greater appetite for reform. By learning from international experiences, Australian policymakers can look at how they can most effectively respond to the distorting impact of short-stays on housing and rental affordability and boost housing supply.

In order to discourage the operation of short-stay rentals and flip as many properties into the long-term rental market as possible, regulations limiting the duration of short-stays or the imposition of financial penalties on landlords must be paired with an effective enforcement and compliance regime which assures the effectiveness of the changes. The federal government can play its role by building consensus with the states and territories around the issue as it has done so before with similar issues, while allowing them to tailor their approach to the conditions of local housing markets, taking into account considerations such as tourism patterns and environmental characteristics. This is not to say that these measures are a silver bullet to solve the current housing crisis, but one of many necessary actions required to properly address a defining challenge of our generation.

The final piece of the puzzle is that the problem might actually be correcting itself. As the cost of living continues to rise, one of the first things people cut out to lower their spending is holidays, and that means Airbnb bookings are declining. The result? Some property owners are putting their properties back on the long-term rental market to seek more stability in their income. This has been an emerging phenomenon in holiday destinations such as the Gold Coast, but capital cities might be insulated from the more extreme demand fluctuations as they may be less reliant on holidaymakers. Meanwhile, it appears that some local governments won’t be waiting – just last week, Melbourne City Council agreed on new measures to curb short-term rentals, including a 180-day-per-year cap and $350 annual registration fee. Any sort of inter-governmental consensus or framework, however, seems slow to come.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.