Introduction: A Brief History of European Defense

As the victorious Allies marched triumphantly over the defeated Axis powers, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stated that an iron curtain had descended on Europe. The Allies were, themselves, an unholy marriage between the capitalist western powers and the communist Soviet Union. Ideological differences caused rising tensions, leading to two major alliances forming: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), consisting of much of Western Europe and the United States of America (USA), and the Warsaw Pact, consisting of the Soviet Union and most communist-aligned governments in Eastern Europe.

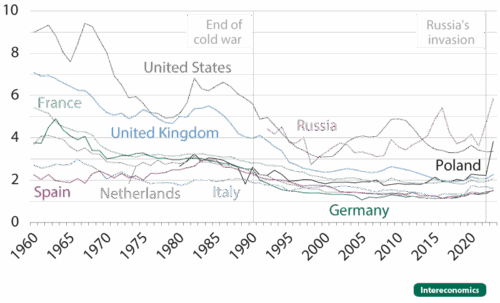

The Cold War lasted from 1945 to 1991, culminating in the fall of the Soviet Union due, in large part, to exogenous shocks in trade with Eastern Europe and the oil industry. This period saw heightened military spending as both sides engaged in an arms race.

Figure 1. Defense spending in % of GDP for selected countries. (Source: SIPRI)

The countries of the European Union (EU) have enjoyed a peace dividend given the lack of a unifying threat post-Soviet collapse. Military spending comes with an opportunity cost, after all, with much money being invested into infrastructure, education and public health. Thus, when Russian troops crossed the border from Belarus into Ukraine in 2022, the EU found itself at odds with a nuclear power, a possible conflict many feared it would be woefully unprepared for.

The German Bundeswehr, for example, has been facing manpower shortages after conscription was stopped along with serious material deficits. This has led to low readiness levels in important weapons systems such as helicopters, vital in providing reconnaissance and medical support, and infantry fighting vehicles, the backbone of modern frontlines.

It appears that the tide has been slowly shifting, especially as American commitment to NATO has become increasingly questionable. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, announced the ReArm Europe program, unlocking an estimated €800 billion in spending centred around increasing combat readiness and supporting Ukraine. This article aims to analyse this complex topic, discussing the political and economic dimensions of ReArm Europe and its ultimate geopolitical implications.

The Economic Dimension

The European Union currently faces opportunities to uplift its defense sector through strong private and public investments. It may, however, find itself challenged by the sustainability of the reindustrialisation of its military sector along with the level of interconnectedness of European and American armies.

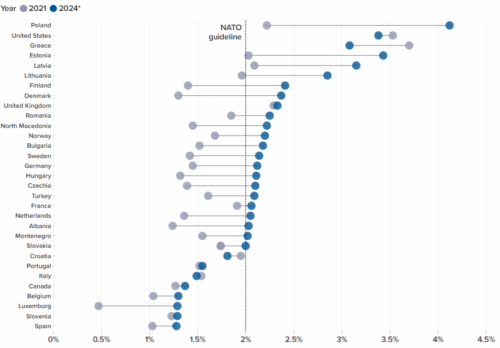

Prior to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, only five NATO countries met the required 2% of GDP allocated to defense. This number has steadily increased, with 22 NATO countries now meeting the requirement following pressure from the USA.

Figure 2. Percent of GDP spent on defense per NATO country. (Source: NATO)

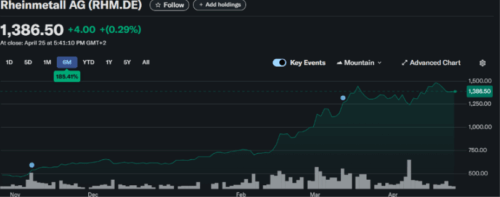

The enthusiasm for rearmament is reflected in both public and private investments. Along with an increase in military spending, an estimated €150 billion in loans has been unlocked for member states through the Security Action for Europe. Several exchange traded funds have been created for private investors while, around the time of the announcement of ReArm Europe, European defense share prices for firms like Rheinmetall, Saab, Thales, and even the British BAE Systems have risen greatly.

Figure 3. Notable increase in the share price of Rheinmetall in March. This trend has been observed with other defense companies.(Source: Yahoo Finance)

In spite of an increase in military spending, Europe still faces significant quantity issues, especially compared to Russia. Russia has fully adjusted to a wartime economy, with much of its manpower and factories being converted to military use. This has allowed them to outproduce both the USA and Europe in artillery shells despite both, individually, having larger industrial bases. Thus, if Europe hopes to compete, its industry needs to be scaled up. Programs such as the European Defense Industrial Strategy aim to increase collaboration between EU member states and scale up production.

A major criticism of recent European defense policy has been its overreliance on the American military for its defense. While recent initiatives have focused on constructing stronger logistical networks through heavy transport aircraft and cargo ships, Europe still relies on America’s intelligence network and hardware (such as the F-35 fighter jet). One recent focus has been to reduce purchases of American arms by upscaling European industries, to the chagrin of American officials.

The Political Dimension

Europe must navigate political opportunities and threats such as shifting attitudes, France’s nuclear arsenal and bureaucratic challenges such as Germany’s debt brake—a constitutional rule that has strictly limited government borrowing since 2009—in its rearmament efforts.

Internally within many EU member states, enthusiasm for a growing military has been steady. Poland is perhaps the strongest example of this, rapidly increasing its active military personnel to become the third largest NATO military. Poland has a long border with Russian-aligned Belarus, along with the Russian Kaliningrad Oblast. While many question the government’s focus on military amidst a cost of living crisis, according to polls, a majority of Poles support militarization.

France is the only EU country to have its own strategic nuclear arsenal, operated by the Force de dissuasion (Deterrence Force). These nuclear weaponry form a nuclear umbrella, acting as a deterrent to Russian aggression in Eastern Europe. This also gives Europe strategic autonomy from the USA as Washington may hesitate to utilise its arsenal in the case of a hot war. The United Kingdom (UK), while not a part of the EU, also operates its own arsenal, which may become a part of European deterrence.

Finally, perhaps the best representation of the geopolitical shocks within the past few years has been Germany’s loosening of its debt brake. Supported by a two-thirds majority of Germany’s upper house of parliament, a historic constitutional amendment will allow for de facto unlimited borrowing and spending on defense. Germany has historically been fiscally strict which, some argue, has prevented it from building a stronger and more resilient economy. The EU, as a whole, has similar strict fiscal policies. As proven by Germany’s constitutional amendment and the ReArm Europe program, though, riskier spending practices such as debt-driven military procurement are almost guaranteed. With growth will come instability, and only time will tell which force will end up more potent.

Conclusion: Will Europe Stand Alone?

The first half of the 2020s have seen era-defining geopolitical shifts from the COVID-19 pandemic to the Russian invasion of Ukraine to Donald Trump’s second term in office. As America has distanced itself from its allies across the Atlantic, the EU, in an ever precarious position, also finds opportunities to establish itself on the world stage as a power autonomous from the USA. In its rearmament efforts, Europe faces complex economic, political and structural issues which form an interconnected web of opportunities and threats that appears nigh impossible to untangle.

As always, the nuclear spectre continues to loom large over the continent. Militarisation policies in the face of the largest European war since WW2 have the potential to change the trajectories of over 700 million lives. The sudden collapse of the peace dividend and Europe’s ominous return to war reflect Vladimir Lenin’s ageless quote: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

Thumbnail source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/feb/24/no-more-excuses-europe-under-pressure-on-defence-spending-three-years-after-russian-invasion

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.