When financial markets plunge seemingly overnight and investors scramble to sell at any price, we witness what economists call a market panic. In economic terms, a panic is essentially an acute financial disturbance – a sudden, violent downturn marked by crashing asset prices and a climate of fear. Unlike an ordinary market decline, a panic feeds on itself. Psychologically, it is a collective fear response in which anxiety overwhelms rational decision-making. As one analysis notes, initial fear can quickly morph into panic and trigger mass sell-offs driven by emotion rather than reason. In a panic, investors can act almost in unison to dump assets, often irrationally – markets become, in effect, crowds governed by fright.

Notable examples from recent history highlight how panic undermines pure rationality. The 2008 global financial crisis is a prime case: as the U.S. housing bubble burst and major banks verged on collapse, fear took hold across the financial system. What began as concerns over mortgage losses cascaded into a full-scale panic. Investors rushed to withdraw funds and sell stocks, causing liquidity to dry up. In September 2008, with Lehman Brothers’ failure, widespread financial panic set in. Markets were in free fall, forcing governments to intervene with emergency measures to stabilize the system. Clearly, many actions during 2008 were not calmly calculated responses, but panicked reactions driven by a loss of confidence in the very fabric of the economy.

More recently, the March 2020 COVID-19 market crash demonstrated how swiftly panic can grip global markets. As the coronavirus outbreak spread worldwide, stock markets plummeted by over 30% in a matter of weeks. This dramatic slide was widely described as a full-blown pandemic panic, going beyond the logical . Investors reacted to frightening headlines and uncertainty by indiscriminately selling assets, even though the long-term economic impact was not yet clear. Subsequent analysis confirms that the 2020 crash was driven more by fear and sensational news than by sober evaluation of earnings or economic data – one study found the decline was mainly associated with a surge in negative news attention rather than rational expectations of damage. In other words, emotions and herd behavior, not just fundamentals, fueled the sell-off. Markets recovered fairly quickly once extraordinary policy support arrived, but the episode underscored how fragile the veneer of rationality can be during a crisis.

These and other biases (overconfidence turning to over-pessimism, “animal spirits” in Keynes’s famous term) help explain why market behavior often departs from the cool logic assumed in textbooks. Individually, an investor might realize that selling in a blind panic is not optimal – yet collectively, even sophisticated players can get swept up in the emotion of the moment. Information cascades and social dynamics take over: if everyone else is fleeing, the pressure to join is enormous, lest one be the “last one out.” Thus, what might be rational for one person to avoid losses becomes magnified into system-wide irrationality. The outcome is a self-reinforcing cycle: falling prices fuel fear, which leads to more selling, further price drops, and so on.

The impacts of irrational individual investors is not limited to individual portfolio return but influences broader market psychology. With market dynamics being shaped by the collective participation of investors, interaction upon interaction between investors can accumulate to stimulate dramatic market movements.

As social beings, investors are vulnerable to irrational behaviour driven by emotions, perceptions triggered by the behaviours of other investors. Herd mentality is a common phenomenon, where investors blindly follow the crowd in making investment decisions, driven by the belief that others have more information and the fear of missing out or losing money.

As investors see other investors sell or buy shares, other investors will see and follow them unable to think for themselves, snowballing into widespread panic or optimism that creates a feedback loop based on pure emotional contagion rather than logical analysis and decisions. These emotional triggers influence other investors, leading to overvaluation and dramatic swings in prices, potentially to excessive spectrums of overreaction.

Herd Mentality is a common element of Bull Markets and Bear markets. Compound the former’s upwards trends whilst exacerbating the latter’s downturn.

During Bull Markets, investors fall victim to herd mentality to buy at large volumes excessively, driven by optimistic speculations that prices will continue to rise, often leading to overvalued prices. When markets eventually fall, investors often incur significant losses due to the excessive speculation. Notable occurrence of herd behaviour in bull markets is the Dot-Com Bubble, when people were obsessed with internet stocks, buying aggressively without proper due diligence of the companies’ performance and financial outlook prior to the crash.

Herd Mentality is also predominant in Bear Markets, when fear and panic spreads as mass sell-offs trigger other investors to liquidate. Evident in the 1987 Black Monday crash, a synchronised rapid emotional response in the market from crowd panic as Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 22.6% in a day, approximately $500 billion in market capitalisation disappeared.

Figure 4: 1987 Black Monday Crash, partially attributed to self-reinforcing fear contagion. Source: adrofx.com.

These days information is widespread, business gurus and advice shared on the internet and among communities. With the popularisation of unofficial financial advice, retail investors increasingly succumb to group behaviour, following trends without doing their own research. GameStop’s short squeeze in 2021 showcases the impact of collective action of an online community, dramatically influencing market behaviours whilst targeting large institutional investors. Critically, the camaraderie inspired by social media’s conveyance encourages irrational actions, with individuals prioritising social standing over tangible investment prospects.

Often stated financial advice is rational investors should opt for well diversified portfolios. This acts as a natural defense against market volatility, with variability in different regions and asset classes offsetting on another to reduce overall risk.

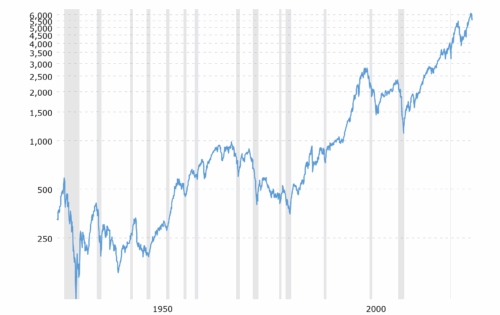

Implicit in this view is a disregard for short-term returns, understanding markets comprehensively incorporating all information, making superior performance difficult. Notably, over the last 30 years the S&P 500 index increased at an average of 10.714% despite this period including multiple market crashes from the Dotcom Crash (2000-2002), to the Global Financial Crisis (2008-2009) and the COVID-19 Pandemic, demonstrating tangible returns for consistency. Further, this denotes the risk of impulsive investment, with investors often reactively adjusting their portfolios capturing downside exposure without benefitting from subsequent rebounds.

Figure 6: S&P 500 over past 30 years, depicts major crashes and subsequent recoveries. Source: www.macrotrends.net.

Thus, long-term investors should disregard current economic conditions, instead viewing economic turmoil through an unbiased outlook focused on long-term growth rather than instantaneous benefit.

A stop loss mechanism is an automated order, utilised by both individual and institutional investors, that will sell a security if it falls below a predetermined price mitigating losses. Through the implementation of a stop loss order, investors essentially predetermine the losses that they are willing to tolerate if there is a downturn. A major benefit of the stop loss is that it removes the ability for emotionality to impinge judgement during downturn, and can provide stability for risk-averse investors (ie pension funds, retirees).

However, significant downsides arise from stop-loss orders. Their predetermined nature allows them to be triggered by temporary volatility resulting in unnecessary sales being made. Further, during crisis induced market illiquidity and volatility, they can trigger at prices much lower than, as there can be no trades being made at the stop price due to lack of counterparties. Despite these negatives, stop loss orders can still be an appropriate risk management tool as they do facilitate exits from the market during volatile periods, thus protecting the investor from their own cognitive biases and associated significant losses

Circuit breakers are also a regulatory tool used to calm the public during volatile times. The first circuit breakers were introduced after the Black Monday stock market crash (1987). For the US circuit breakers apply to the major stock exchanges like NASDAQ and the NYSE. They have 3 levels with levels 1 and 2 triggering a 15 minute trading halt while level 3 will result in a market wide shutdown for the rest of the trading day.

Further, history has shown the importance of influential financiers in stepping in and acting as de facto central banks, quelling market uncertainty. A clear example occurred during the panic of 1907, when J.P. Morgan intervened, preventing the market from imminent collapse. This preceded the creation of the US federal reserve, with many of these rolls now falling under their purview.

Figure 7: J.P. Morgan, key restorative force in ensuring stability in early US financial markets. Source: www.britannica.com.

As financial systems have matured, this market-shoring role has increasingly been institutionalised with central banks and government regulators bearing the burden.

For example, following the GFC in 2008, significant regulatory reforms have been implemented to improve market stability. This mainly took place through the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act enacted by former Presidents george W. Bush and Barack Obama. Mainly targeting shadow banking and over the counter (OTC) derivatives by implementing stricter regulations to reduce the potential for systematic risk, this changes exemplify modern modifications to the financial system to combat sentiment based market volatility. Hence, increasingly the calming force of industry figureheads has been replaced by heightened regulation.

Whilst many fundamental economic and financial principles espouse investor rationality, market behaviour especially during periods of uncertainty are often driven by investor biases. This presents both risks, increasing volatility magnitude, but also opportunities with market participants more cognisant of their baisses and understanding of underlying asset valuations able to benefit from temporary mispricings.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.