Greenland, Australia, Ukraine and the Democratic People’s Republic of the Congo- It’s difficult to construct a more unlikely grouping, unaligned politically, socially or geographically, have similarly drawn Trump’s focus in his ‘America First’ crusade to reorder the US’s economic, territorial and security norms. All rich in rare-earth minerals, Trump has framed them as ideal for providing favourable access to resources for US users. Like many Trumpian policies, this focus could easily be dismissed as either a cash-grab, aiming rewarding supporters who maintain substantial equity stakes firms likely to be engaged, or simply another faucet in his maximal pressure negotiation strategy, employing gamesmanship pursuit of the optimal deal.

Figure 1: Presidents Trump and Zelensky

Source: The Conversation

However, this outlook ignores the deeper nuances driving the broad US bipartisan consensus to strengthen their rare-earth supply chains. With measures to develop US rare-earths surviving the mercurial nature of shifting US administrations and Trump’s limited attention span, could these recent actions pertain to a more significant industrial shift rather than mere political bluster?

Consisting of an array of elements critical to high-performance modern technology, rare earth minerals have increasingly come to signify the US’s industrial dependence on Chinese production. Somewhat of a misnomer, rare earth minerals are actually quite abundant, including minerals such as Cerium which ranks as the 25th most common in earth’s crust. Instead of rarity, it’s typically the availability and development of extraction, refinement and downstream processing which restricts access.

With isolation techniques applicable to rare-earths pioneered through the Manhattan project, which necessitated highly precise refinement for Uranium and Plutonium, the US began with a dominant industry position. Capitalising on this, America poured substantial resources into production dominating worldwide production throughout the 1960s to mid 80s. Principally, the development of Mountain Pass mine, owned by American firm Molycorp, produced over 25,000 mT of purified rare-earth ore representing over 70% of the world’s total rare-earth production, whilst capturing 99% of internal heavy rare-earth demand.

Figure 2: Mountain Pass Mine, California

Source: Mining Review Africa

Following the collapse of the USSR, dampened security concerns alongside an unbalanced competitive landscape decimated the US industry.

As is endemic in extractive industries, the rare-earth mining and refinement processes contributed to considerable environmental degradation. Notably, from Mountain Pass’s inception waste spills were commonplace. These concerns were underscored in the 1990s when increasing scrutiny from the Environmental Protection Agency uncovered hundreds of thousands of litres of illegal waste-water discharge, containing contaminants including radiological compounds and toxic hydrogen sulfide. With broad global amiability following the USSR’s collapse, political impetus formed to globalise extraction, outsourcing ecological risks to countries lacking environmental scrutiny.

Figure 3: Chinese producers’ environmental regulation advantage

Source: Institute of Energy for South-East Europe

Concurrently to growing opposition to the US rare-earth industry, China identified it as a key industry for development. Recognising the significance of rare-earths, in the 1980s Chinese government bodies undertook decisive action, committing significant resources to both rare earth element production and research. Complementing this, the Chinese government encouraged domestic firms to partner with international leaders on both upstream and downstream processing projects. This facilitated the expedient transfer of intellectual property to domestic users, expediting the domestic industry’s progression.

Figure 4: Early US dominance are rapid decline

Source: United States Army

This rapid expansion in Chinese rare earth capabilities had significant consequences. Not beholden shareholder expectations of returns or stringent environmental regulation, fierce price competition ensued, forcing international competitors from the market. Ultimately, this left China with a near monopoly, extracting north of 95% of the world’s rare-earth oxides in 2010.

Exploiting this uncontested upstream position, China quickly moved to grow domestic downstream industries. Targeting key products such as high-performance neodymium magnets (critical in defense applications) state run companies sought to acquire international producers. A significant instance of this was the acquisition of Magnequench, the primary US producer of high-tech rare earth magnets, in 1995 by firms including China National Import & Export Corporation. Enabling this was lax oversight, failing to properly uncover and scrutinise underlying nationalist ties of the acquiring consortium instead only seeing the domestic frontman. Upon the cessation of a 5 year guarantee to maintain the US operations, all machinery were transferred to China, decimating both the US industry and kickstarting China’s preeminence in the space.

Source: Baker Institute

Further supporting this, China employed tiered export restrictions, with quotas on the quantity of non-value added minerals that could be exported. By holding a near monopoly on rare-earth oxides, this necessitated global producers in downstream industries relocating production lines to China. Whilst perhaps initially providing mutual benefit by lowering costs through an eager regulatory environment, this further facilitated intellectual property transfer.

The confluence of these factors left China with a commanding position over the rare earth landscape, with 61% of the ore output and 91% of processing capacity in 2025.

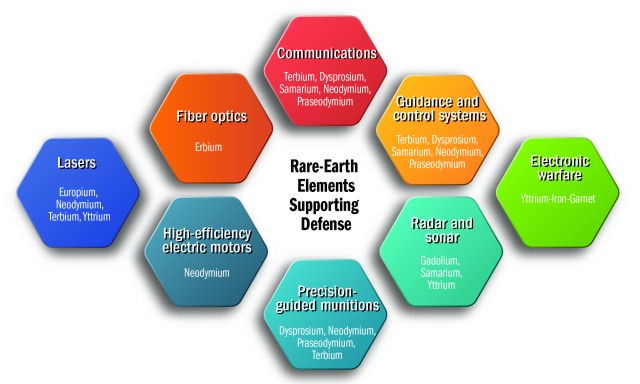

Although first isolated in 1794, rare earths would not become commercially used until the late 1880s. However, with exponential growth in their use over the last half-century, rare-earth minerals have become critical in a range of applications. Vital in a range of high-performance products ranging from magnets to alloys to lasers, they have become critical in both civil and defense applications.

Figure 6: Wide ranging applications of rare-earth elements

Source: United States Army

Their necessity in an array of defense products from jets to submarines has drawn increased focus to securing their supply chain. For instance, an F-35 requires over 400 kg of rare earth components, whilst larger products like Destroyers and Submarines require over 2400 kg and 4200 kg respectively. Moreover, society’s increasing electrification has accelerated demand, with nearly all electronics, including renewables requiring significant quantities of rare-earth minerals.

Thus, the US has essentially become reliant on a single concentrated supplier for both defense and broader economic needs.

As early as 2010, China began to employ their rare earth industrial might in geopolitical coercion. Ostensibly responding to a ‘fishing dispute’ where a Chinese fishing trawler collided with a Japanese coast guard vessel off the Senkaku islands, China placed an embargo on rare earth exports to Japan, imperilling its advanced electrical product industry. Ultimately, this restriction would be lifted upon the release of the fishing ship’s captain, displaying the efficacy of these restrictions in leveraging concessions from international disputes.

Figure 7: Territorial dispute between China and Japan

Source: Officer’s Pulse

Whilst minor restrictions had been imposed on the US since 2023, with exports of both rare earth products and associated technologies restricted, substantial impositions have only recently eventuated. These prior restrictions however, have served their purpose, guarding China’s supremacy by limiting international stockpiling increasing dependency and harming alternative international projects.

Responding to pressure from Trump’s tariffs, in recent weeks China has drastically constricted the US’s access to rare earth products. Via classifying a range of rare-earth products in its opaque export control system, where licenses must be applied for to export any listed good, China has curbed global supply of rare earth minerals; gallium exports volume is down 75%, germanium 53% and antimony 62%. Moreover, unofficially the process has been slowed to glacial pace, in spite of a standard application period of 45 days US importers have reported additional delays and even cancellation of orders suggesting China is applying pressure through both official and back-room means.

Consequently, China has persistently illustrated that its pivotal position in the US rare-earth supply chain poses an undeniable risk to US foreign policy and economic functioning.

Cognisant of decades of atrophy, the US and allies have progressively sought to combat China’s chokehold of supply. Being an early victim of coercion, Japan proactively supported alternatives, supporting Lynas Rare Earth, the only significant miner and refiner outside of China. Struggling in 2010, unable to secure financing for its Malaysian refinery, Lynas was rejuvenated by financing from Japanese conglomerates and state-owned Japan Oil. With favourable terms allowing the suspension of interest and principal payments at Lynas’s discretion alongside guaranteed purchase contracts, this represented a coordinated Japanese effort to safeguard Lynas from rare-earth price manipulation.

Figure 8: Australia’s first rare-earths processing facility owned by Lynas

Source: PV Magazine

Today, Japan has alleviated its supply concerns with Lynas supplying one third of its rare earth needs and 90% of its light rare earth requirements. Whilst not currently a salvation for the US’s needs, this presents a clear blueprint for the measured and sustained actions to repair America’s hollowed out rare earth industry.

Although slower to react, consecutive US administrations have also targeted supply chain diversification. In conjunction to parallel investments in Lynas, where the US Department of Defense sunk $US 258 million into establishing a heavy rare earth refinery in Texas, domestic production has been restarted at Mountain Pass mine alongside new facilities to produce niobium in Nebraska.

Simultaneously, MP Materials, the offshoot of the now defunct Molycorp which now controls the Mountain Pass facility, has ramped up both Californian refinement and emerging magnet production. Spurring this, the imposition of 125% reciprocal Chinese tariffs and export restrictions have prompted concerns over long-term shortages, encouraging US firms to consider broader reliability over simple unit cost when choosing suppliers.

Support for these ventures has been broadly bipartisan, with the MP Materials Mountain Pass being funded through Biden era grants. Somewhat the exception in America’s polarised political landscape, the commitment from across the political spectrum has leant vital stability to otherwise volatile government funding processes.

Risks here however remain evident, following the 2010 Senkaku uncertainty, domestic processing elicited notable political commitments. Largest amongst them being Hitachi’s $US 60 million state of the art rare earth magnet facility which shuttered in 2015, after only two years of operation tensions eased, with Hitachi instead entering a Chinese joint venture. Therefore any reactionary supply measures must be willing to offer prolonged support regardless of immediate conditions.

Figure 9: Key Ukrainian mineral deposits Source: BBC

Extending past alternate domestic avenues to increase production, Trump has increasingly sought to leverage international relations to secure favourable access to rare earths. Most prominent amongst these has been the potential Ukraine deal, which whilst unclear, seems to involve US firms receiving access to plentiful Ukrainian deposits, encompassing both rare earths and other critical minerals.

Further, sporadic reports continue to emerge surrounding large commitments of Congolese mineral deposits. With the Congolese president offering compelling terms to the US contingent on security guarantees to combat extremist group M23. Critically, Trump loyalist and former chief of private security organisation Blackwater Erik Prince, has travelled to region to discuss terms, suggesting broad interest from key figures within Trump’s inner circle.

In Australia, the potential for rare earth based deals has also been popularised. Both Prime Minister Albanese and opposition leader Dutton have raised the prospect of rare earth concessions to incentivise tariff respite. Whilst these negotiations remain remarkably poorly defined, it’s entire proposition relies on the importance of US rare-earth diversification.

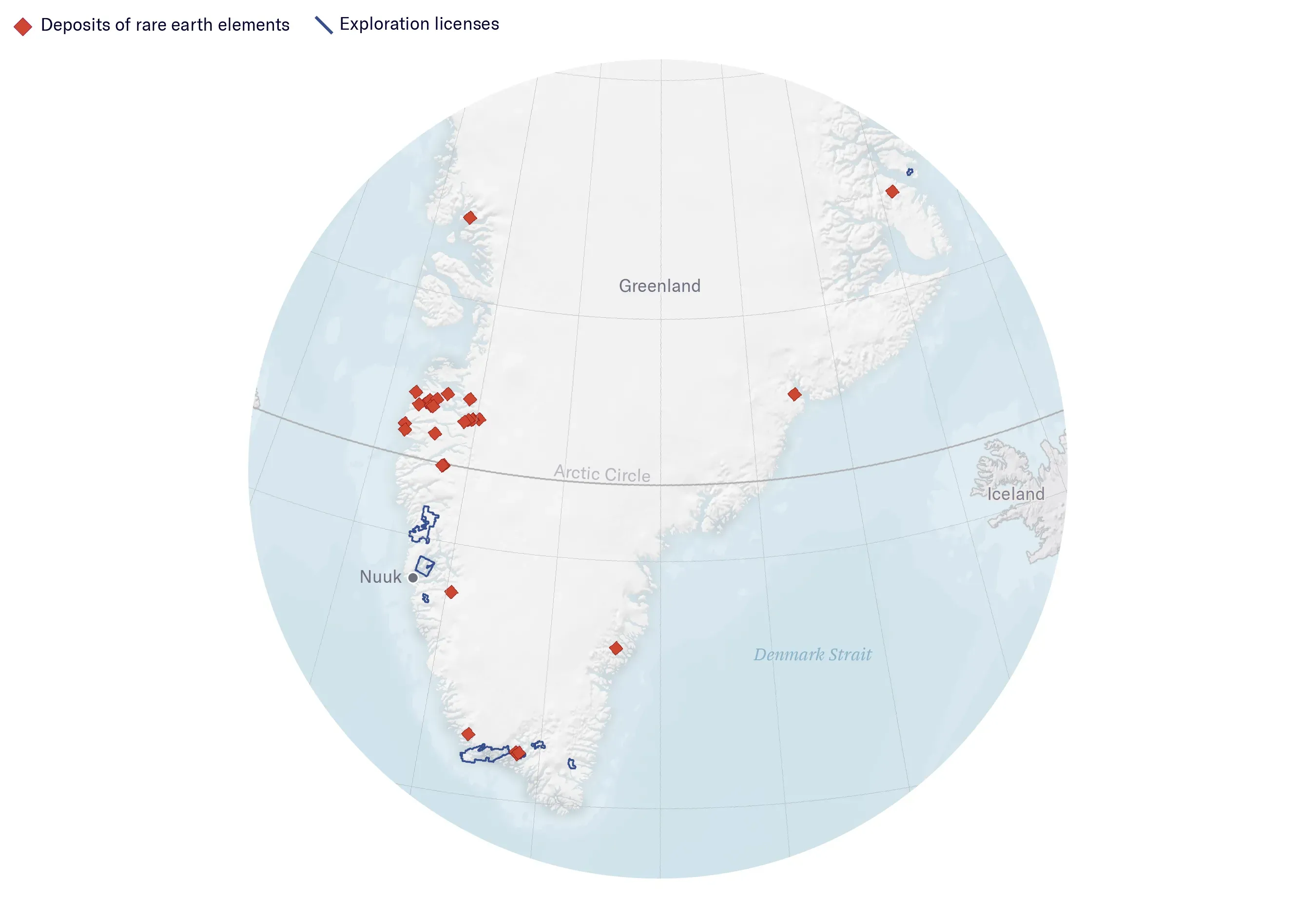

Figure 10: Greenland’s abundant untapped rare-earth deposits Source: Pulitzer Center

Perhaps the most dubious of Trump’s resource fascinations is his Greenland dream. Despite proposing the acquisition predominantly on defense grounds, he has repeatedly opined for Greenland’s vast resource exploitation opportunity. Indeed, Greenland holds some of the largest rare earth element deposits globally, however remains untapped due to stringent environmental regulation.

Thus, rare-earth minerals clearly act as a key motivator guiding Trump’s political posturing, presenting both opportunities and risks for potential targets.

Whilst perhaps partially seeking to enrich his close supporters, it is clear Trump’s actions are a function of broader US sentiment supporting the fortification of their supply chain. Further, far from an unachievable pipe dream, precedent supports the rapid resuscitation of the rare-earth industry.

Despite short-term limitations of US suppliers to meet defense, much less wider consumer demand for rare earths, China’s swift growth and Japan’s diversification suggest substantial improvement is attainable in mere years. However, any success must be predicated on clear oversight and sustained support, with attempts to bypass challenges potentially imperiling the entire project.

ABC News (Australia). (2025, April 16). IN FULL: Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton clash in ABC NEWS Leaders Debate. YouTube; Australian Broadcasting Company. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VfkVB2eX7U

Abdujalil Abdurasulov, & Plummer, R. (2025, February 24). Why is Ukraine negotiating a minerals deal with the US? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c20le8jn282o

Aikman, I. (2025, February 26). Ukraine minerals deal: What we know so far. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn527pz54neo

Ange Adihe Kasongo. (2025, April 4). After tariffs, US dangles billions of dollars in Congo mineral investment. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/after-tariffs-us-dangles-billions-dollars-congo-mineral-investment-2025-04-03/

Bloomberg. (2025). Chinese rare earth shipments held up as trade war upends exports. Mining Weekly; Bloomberg. https://www.miningweekly.com/article/chinese-rare-earth-shipments-held-up-as-trade-war-upends-exports-2025-04-11

BURMEISTER, T. (2024, September 11). An Asian elephant calf was born at Zurich Zoo and its name will start with the letter Z. Elko Daily Free Press; Elko Daily. https://elkodaily.com/news/local/business/mining/article_fe410bb2-5f5c-11ef-9879-6b2064c7584f.html

Cho, R. (2023, April 5). The Energy Transition Will Need More Rare Earth Elements. Can We Secure Them Sustainably? State of the Planet; Columbia Climate School. https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2023/04/05/the-energy-transition-will-need-more-rare-earth-elements-can-we-secure-them-sustainably/

Clair, J. S. (2006, April 7). The Saga of Magnequench. CounterPunch.org; CounterPunch. https://www.counterpunch.org/2006/04/07/the-saga-of-magnequench/

Cornish, L. (2015, October 13). Imminent shutdown for Molycorp Mountain Pass mine. Miningreview.com. https://www.miningreview.com/top-stories/molycorp-mountain-pass-mine-shutdown-imminent/

Funk, J. (2025, April 18). America’s only rare earths mine is hearing from lots of anxious companies: “Selling our valuable critical minerals under 125% tariffs is neither commercially rational nor aligned with America’s national interests.” Fortune; Fortune. https://fortune.com/article/americas-only-rare-earths-mine-mp-materials-mountain-pass-mine-us-china-trade-war-tariffs/

Gan, N., & Liu, J. (2025, April 15). China has a powerful card to play in its fight against Trump’s trade war. CNN; CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/04/15/business/china-trumps-trade-war-rare-earth-intl-hnk/index.html

Goldman, J. (2025). The U.S. Rare Earth Industry: Its Growth and Decline. Cambridge.org; Cambridge University Press. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-policy-history/article/us-rare-earth-industry-its-growth-and-decline/BC6E0E8EFC02B7C781F13C58CC8DC6E1&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1745251763823390&usg=AOvVaw2ASgoY22xUz4kqceOwoR5o

Green Car Congress. (2020, April 15). USA Rare Earth acquires US rare earth permanent magnet manufacturing capability from Hitachi; mine-to-magnet. Green Car Congress. https://www.greencarcongress.com/2020/04/20200415-rareearth.html

Hancock Prospecting. (2024, April 13). Magnate Gina Rinehart Moves into Rare Earth Metals – Hancock Prospecting PTY LTD. Hancock Prospecting PTY LTD; Hancock Prospecting PTY LTD. https://www.hancockprospecting.com.au/magnate-gina-rinehart-moves-into-rare-earth-metals/

Hurst, C. (2010). China’s Rare Earth Elements Industry: What Can the West Learn? Institute for the Analysis of Global Security (IAGS). Institute for the Analysis of Global Security. http://www.iags.org/rareearth0310hurst.pdf

Illeborg, J. (2025, April 13). Geologist warns prospect of a mineral bonanza in Greenland is a mirage. Cbsnews.com; CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/geologist-warns-prospect-mineral-bonanza-greenland-mirage-60-minutes/

Institute of Energy for South-East Europe. (2025). China’s Rare Earth Export Ban Is Backfiring. Iene.eu; Institute of Energy for South-East Europe. https://www.iene.eu/chinas-rare-earth-export-ban-is-backfiring-p7260.html

Jackson, L., & Lv, A. (2025, April 21). China’s export controls are curbing critical mineral shipments to the world. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-export-controls-are-curbing-critical-mineral-shipments-world-2025-04-20/

Jamasmie, C. (2025, April 17). Blackwater founder and Trump ally strikes mineral security deal with Congo. MINING.COM. https://www.mining.com/trump-ally-prince-strikes-mineral-security-deal-with-congo/

James, C. (1999, August 29). Separation of Rare Earth Elements. American Chemical Society. https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/earthelements.html

Kay, J. (1995, December 5). Unocal faces $489,000 fine. SFGATE. https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/unocal-faces-489-000-fine-3118696.php

Lee, J. (2021, July 26). Rare Earths Explained. Milken Institute Review. https://www.milkenreview.org/articles/rare-earths-explained

Lynas Rare Earths. (2023, August). U.S. DoD Strengthens Support for Lynas U.S. Facility. Lynas Rare Earths; Lynas Rare Earths. http://lynasrareearths.com/u-s-dod-strengthens-support-for-lynas-u-s-facility/

Martins, T. (2023, December 8). A Brief History of US-China Rare Earth Rivalry | Geopolitical Monitor. Geopolitical Monitor; Geopolitical Monitor. https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/a-brief-history-of-us-china-rare-earth-rivalry/

Michot Foss, M., & Koelsch, J. (2022, December 19). Of Chinese Behemoths: What China’s Rare Earths Dominance Means for the US. Baker Institute; Baker Institute. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/chinese-behemoths-what-chinas-rare-earths-dominance-means-us

National Mineral Information Center. (n.d.). Rare Earths Statistics and Information | U.S. Geological Survey. Www.usgs.gov; National Minerals Information Center. Retrieved April 21, 2025, from https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/rare-earths-statistics-and-information

Officers Pulse. (2024). Senkaku islands dispute – Officers Pulse. Officerspulse.com. https://officerspulse.com/2021/03/02/senkaku-islands-dispute/

Park, S., Tracy, C. L., & Ewing, R. C. (2023). Reimagining US rare earth production: Domestic failures and the decline of US rare earth production dominance – Lessons learned and recommendations. Resources Policy, 85, 104022–104022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104022

Parman, R. (2019, September 26). An elemental issue. Www.army.mil; US Army. https://www.army.mil/article/227715/an_elemental_issue

Rachman, J. (2023, August 15). Japan Might Have an Answer to Chinese Rare Earth Threats. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/08/15/japan-rare-earth-minerals-green-transition-china-supply-chains/

Seth, N. (2024, August 15). How to Diversify Mineral Supply Chains – A Japanese Agency has Lessons for All. New Security Beat. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2024/08/how-to-diversify-mineral-supply-chains-a-japanese-agency-has-lessons-for-all/

Tatsuya Terazawa. (2023, October 13). How Japan solved its rare earth minerals dependency issue. World Economic Forum; World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/10/japan-rare-earth-minerals/

Team, S. (2025, April 15). China’s rare earth restrictions threaten US defence – Sharecafe. Sharecafe – Serving up Fresh Finance News, Marker Movers & Expertise. https://www.sharecafe.com.au/2025/04/16/chinas-rare-earth-restrictions-threaten-us-defence/

The White House. (2024, September 20). FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Takes Further Action to Strengthen and Secure Critical Mineral Supply Chains | The White House. The White House; The White House. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/20/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-takes-further-action-to-strengthen-and-secure-critical-mineral-supply-chains/

Zadeh, J. (2025, April 21). MP Materials Halts Rare Earth Exports to China Following 125% Tariffs. Discovery Alert. https://discoveryalert.com.au/news/mp-materials-rare-earth-supply-china-2025/

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.