The tiny isolated nation of Nauru was once a tropical paradise. Tucked away in the Central Pacific, Nauru’s verdant palm trees, white-sand beaches and friendly population entranced early European explorers, a sight that led Captain John Fearn to name it Pleasant Island.

Hidden within Nauru’s interior, however, is a curse that left the island a shell of its former self. Nauru was once extremely wealthy, boasting the second highest GDP per capita in the world in the 1970s, but beneath the veneer of this economic success was a cautionary tale on the effects of greed and gluttony. Most of Nauru has since become inhospitable and polluted, with the once beautiful island now being littered with trash heaps, rusty cars and run-down houses.

Nauru’s riches to rags story is equally complex and compelling, highlighting the importance of sustainable development and proper resource management. The recent history of Nauru revolves around a resource that has, since its discovery, evolved into Nauru’s boon and curse: phosphate.

The Past: A History of Nauru and the Curse

Nauru has been inhabited by Micronesian and Polynesian settlers for over 3,000 years. The island was divided among twelve clans, a defining feature of Nauru still reflected on the twelve-pointed star on its flag. A civil war broke out in 1878 after an altercation occurred during a wedding, likely influenced by the introduction of alcohol and firearms on the island. Following this, Nauru’s population dropped from 1,400 to 900. By 1888, German intervention forcibly ended the civil war, annexing Nauru.

Phosphate has always played an important role in Nauru’s development. Nauru’s phosphate reserves were built up over time by a complex process of mineralisation. Surveyors from the German administration discovered that the island was made mostly out of phosphate stored in limestone pinnacles. Phosphate mining on Nauru started in 1906 with the German Pacific Phosphate Company. Phosphate is mainly used as fertiliser, which became especially important during the concurrent Industrial Revolution to feed the world’s growing population.

During World War 1, Australian troops captured Nauru, asserting a joint British-Australian-New Zealand mandate over the territory. The British administration created the British Phosphate Commission (BPC). The Japanese occupied the island in 1942 and momentarily took over phosphate mining operations. Before the Japanese garrison surrendered, Nauru underwent a brutal occupation. Nauru gained independence in 1968 from the British, Australian, and New Zealander triumvirate. The BPC was transferred to Nauru and became known as the Nauru Phosphate Corporation (NPC).

The Rush: Blessed by Phosphate

Nauru’s tragedy links together phosphate mining, grand skyscrapers and a failed musical. The NPC proved to be extremely enriching to Nauru and its constituents. Phosphate exports were definitely a boon in the 1970s. Australia and New Zealand were heavily reliant on Nauru’s cheap and high quality phosphate for national development, with 80% of Australian cropped area requiring phosphate due to Australian soil being classified as low-fertility.

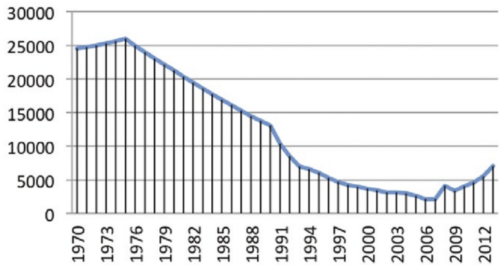

Figure 1. Nauru GDP per capita in US$

Nauru’s overreliance on phosphate mining brought benefits to the country. The population grew wealthy as a result and had one of the highest GDP per capita in the world. Nauruans lived in luxury. Despite Nauru barely having any paved roads, citizens spent government handouts on sports cars. One police chief, in particular, bought a Lamborghini but found that he was unable to fit in the front seat.

The Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust (NPRT) was established to ensure that Nauruans will have income even after the phosphate ran out. The trust was horribly mismanaged due to several failed investments and corruption. The Nauru House in Melbourne was one of the NPRT’s investments, costing $38.5 million to build. In 2004, it was sold to Queensland Investment Corporation to pay off national debts. The NPRT also funded Leonardo da Vinci: A Portrait of Love, a play about an illicit love affair between Leonardo da Vinci and the Mona Lisa. The play was critically panned and bombed, losing $7 million for the Nauruans.

Eventually, Nauru’s phosphate reserves ran out, leaving behind a degraded biodiversity compounded by the introduction of invasive species and a destruction of Nauru’s agricultural land. Nauru became heavily dependent on food imports, mostly canned goods, leading to extremely high obesity rates. The value of the NPRT plunged from $1.3 billion in 1990 to just $0.3 billion in 2004.

Figure 2. A phosphate mine in Nauru. Nauru’s interior is dotted with limestone pinnacles.

The Present: Can Nauru Regain its Riches?

Nauru’s history of riches to rags is a unique example of how unsustainable growth can destroy a nation. Nauru today is a far cry from the Pleasant Island that John Fearn spotted, with the most noticeable features of its interior being old mining equipment and limestone pinnacles.

Nauru is extremely small, being the third smallest country in the world by landmass at only 21km2 and a population of around 13,000. Despite the many challenges it has and is currently facing, Nauru has managed to re-emerge as a high-income country. Government revenue has boomed in recent years, though the methods used to achieve these are dubious.

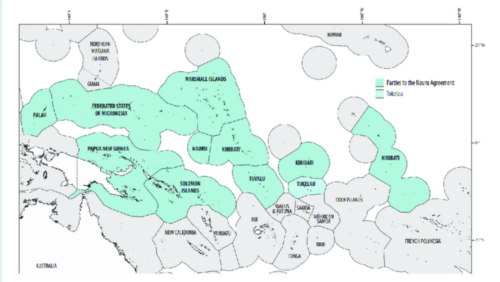

Nauru’s two main revenue streams are fishing licences and the controversial Regional Processing Centre (RPC). Nauru, similar to other Pacific Island nations, has a massive exclusive economic zone (EEZ), meaning that it is able to licence its territorial waters for fishers, bringing in over $70 million in 2019.

Figure 3. EEZ of Nauru, among other countries

Nauru also gets a significant portion of its revenue from the RPC, which is funded by Australia. The RPC is an offshore location for the processing of refugees. It is estimated that Nauru received $133 million from the site in 2023-24, making up a big portion of the nation’s economy. However, concerns have been raised that the revenue from the RPC has gone into the hands of very few landowners and politicians. Furthermore, there have been many human rights violations in the RPC, with refugees suffering physical and mental abuse. As a result, many have called for the shuttering of the RPC.

While Nauru has been able to benefit from fishing licences and the RPC as income sources, the lack of diversity in the Nauruan economy leaves it vulnerable to changes in either fish prices, which can impact demand for fishing licences, and any decision by the Australian government to close the RPC.

Conclusion

As the dust settles on Nauru’s phosphate boom, an important question arises: did Nauru’s phosphate reserves curse the island?

A resource curse refers to the phenomenon wherein resource-rich countries tend to underperform economically. This likely arises as a result of weak institutional capacity, where much of the wealth from natural resources gets corrupted or squandered. Nauru’s phosphate reserves did not inherently cause the country to suffer; in fact, Nauru flourished from the wealth that its phosphate exports brought in. Time and time again, this wealth was wasted on problematic investments, with phosphate reserves being harvested until the island itself was unrecognisable. Its gluttonous institutions, perhaps, consisting of ill-advised fund managers and greedy politicians may have been the real curse of Nauru.

Despite its troubled history, Nauru is still surviving. Its recovery is unstable and reliant on external factors, meaning that, especially with increasing sea levels threatening Nauru’s survival, the resilience of Nauru’s twelve clans will once again be tested.

References:

(2013, February 18). The Nauru War — Inside the Smallest Armed Conflict in History. Military History Now. https://militaryhistorynow.com/2013/02/18/the-nauru-war-the-smallest-conflict-in-history/#google_vignette

(2023). How a tiny island became one of the richest countries in the world and then lost it all in 40 years. Nauru House. https://nauru-house.mystrikingly.com

(n.d.). “I have seen so many funerals for such a small island”: The astonishing story of Nauru, the tiny island nation with the world’s highest rates of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes.co.uk. https://www.diabetes.co.uk/in-depth/i-have-seen-so-many-funerals-for-such-a-small-island-the-astonishing-story-of-nauru-the-tiny-island-nation-with-the-worlds-highest-rates-of-type-2-diabetes/#:~:text=The%20colonial%20trade%20links%20Nauru,were%20largely%20inspired%20by%20necessity.

Bineth, J., & Shannon, S. (2016, June 13). Boy bands and musicals: The secret history of Nauru and its lost wealth. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/earshot/the-secret-history-of-nauru-and-its-lost-wealth/7496620

Buckley, K.D. (1987). [Review of the book The Phosphateers: A History of the British Phosphate Commissioners and the Christmas Island Phosphate Commission, by Maslyn Williams, Barrie MacDonald]. New Zealand Journal of History 21(2), 294-295. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/872385.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2024, August 13). Nauru. cia.gov. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nauru/#:~:text=Germany%20forcibly%20annexed%20Nauru%20in,profits%20from%20the%20phosphate%20deposits.

Cox, J. (n.d.). The money pit: an analysis of Nauru’s phosphate mining policy. ANU. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/e4c7edda-aa4e-4275-ad35-c900748911fd/content

DVA (Department of Veterans’ Affairs). (2021). Capture of German outposts in the Pacific 1914, DVA Anzac Portal. https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/ww1/where-australians-served/captured-german-outposts

DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). (n.d.). Nauru country brief. DFAT.gov.au. https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/nauru/nauru-country-brief#:~:text=Nauru%20is%20one%20of%20the,style%20parliamentary%20system%20of%20government.

Fernando, J. (2022, September 29). Resource Curse: Definition, Overview and Examples. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/resource-curse.asp#:~:text=The%20term%20resource%20curse%20refers

Gale, S. J. (2019). Lies and misdemeanours: Nauru, phosphate and global geopolitics. The Extractive Industries and Society, 6(3), 737–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2019.03.003

Hasham, N. (2015, November 3). UN’s Nauru verdict: A poor, isolated island ravaged by phosphate mining. The Sydney Morning Herald; The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/uns-nauru-verdict-a-poor-isolated-island-ravaged-by-phosphate-mining-20151102-gkp145.html

Howes, S., & Surandiran, S. (2021, April 11). Nauru: riches to rags to riches. Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. https://devpolicy.org/nauru-riches-to-rags-to-riches-20210412/

Hughes, H. (n.d.). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY From Riches to Rags What Are Nauru’s Options and How Can Australia Help? https://www.cis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ia50.pdf

Ministry of Finance -Treasury Government of Nauru Quarterly Budget Performance Report Quarter 4, 2018-19 Outturn report. (2019). https://naurufinance.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Government-of-Nauru-Quarter-4-Financial-Report-2018-19.pdf

Morris, J. (2023, August 29). As Nauru Shows, Asylum Outsourcing Has Unexpected Impacts on Host Communities. Migration Policy. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/nauru-outsoure-asylum#:~:text=The%20government%20estimates%20that%20money,resettlement%20contract%20remains%20quite%20lucrative.

Orr, R. (2023, December 28). The misery of Pleasant Island. The World Journal; The World Journal. https://worldjournalnewspaper.com/the-misery-of-pleasant-island/

Parke, E., & Maloney, R. (2024, April 9). First details emerge of rapidly filling Nauru detention centre following four boat arrivals in six months. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-04-10/asrc-concerns-human-rights-nauru-detention-centre-asylum-seekers/103686082

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust Act 1968. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://ronlaw.gov.nr/nauru_lpms/files/acts/be53123090748e90e529bb80b165712d.pdf

Tanaka, Y. (2010, November 8). Japanese Atrocities on Nauru during the Pacific War: The murder of Australians, the massacre of lepers and the ethnocide of Nauruans. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. https://apjjf.org/yuki-tanaka/3441/article

US Department of State. (n.d.). Nauru (09/06). 2009-2017.State.gov. https://2009-2017.state.gov/outofdate/bgn/nauru/74212.htm

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.