In an era of unprecedented transformation within Australia’s labour market, students and professionals face the challenge of securing their places in a workforce marked by fluctuating demands, dynamic skill requirements, and evolving economic dynamics. The volatility within Australia’s Labour market can be seen in our unemployment rate. In April 2023, Australia’s unemployment rate hit a record low of 3.5%. However, this historic low is unlikely to be sustained due to factors such as rising inflation, an increasing cash rate, and structural changes in the Australian economy. With this in mind, what can we expect going forward from the Australian labour market, and importantly how have recent policy decisions impacted the mismatch of supply and demand within saturated markets?

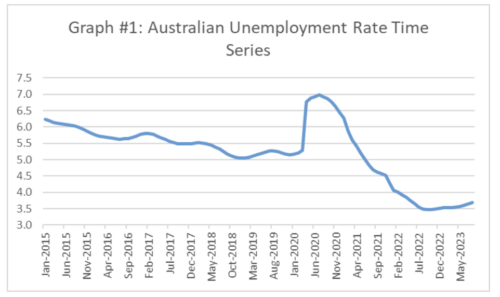

As shown in Figure 1, Australia has enjoyed steadily declining unemployment rates since 2015, accompanied by stable inflation and favourable global economic conditions. The abrupt rise in unemployment to 7% in March 2020 was a consequence of COVID-19 lockdowns. After the pandemic, a surge in demand and discretionary spending led to unemployment falling to 3.5% in August 2022.

Source: ABS

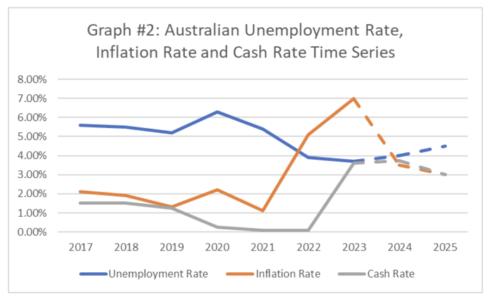

However, the situation changed as inflation soared to 7.8% due to increased domestic retail demand and the return of international buyers, forcing the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to raise interest rates to 3.5% (Figure 2). This policy shift is likely to result in lower inflation and a potential increase in unemployment from these historic lows. The relationship between unemployment and inflation, often associated with the Phillips curve, remains relevant for non-cost push inflation. The RBA forecasts that unemployment will gradually rise back to around 5% by late 2025.

Source: RBA Historical Inflation, RBA Economic Outlook. Note yearly values taken from March values.

So with rising rates, lowered inflation and slowly increasing unemployment, how resilient will Australia’s Labour market be. And in particular how will this affect students and professionals, on their quest to be another member of the skilled workforce? The job market, especially for skilled labor, is closely tied to university education. Higher education enhances employment prospects and increases the likelihood of securing full-time employment. However, recent government policies have led to price increases in university education, particularly in humanities subjects. For instance, there has been a 28% increase in commerce course fees and a substantial 113% increase in humanities course fees. This move is aimed at aligning education with the demands of skilled industries, but it places a significant financial burden on students.

It’s essential to note that students do not pay these fees upfront. The Australian government offers the HECS-HELP (Higher Education Contribution Scheme – Higher Education Loan Program) scheme, providing students with education loans or discounts on higher education expenses. Currently, over $68.7 billion in loans have been granted by the federal government under this scheme, shared among 2.9 million people. Of these, 1.3 million individuals have accumulated debts exceeding $20,000.Due to this loan system, it comes as no surprise that critics point to the fact that many students decide their degree independent of the cost. How many aspiring authors are going to consider switching to Math due to an increase of a few thousand in an interest free loan with favourable terms? Perhaps other mechanisms are needed by the Government to fix the existing imbalance.

The Australian government has several policy options to tackle the skills and workforce mismatch. One approach is to offer subsidies for degrees in high-demand fields, making these degrees more affordable and encouraging students to pursue careers in these areas. However, this might have limitations due to the price inelasticity of degrees.

Another viable option is to invest in vocational education and training (VET). VET programs provide specific job-related skills and can attract those on the fringe of tertiary education, particularly in trade-based skills, which are in demand due to the energy transition. Cheaper vocational training, combined with apprenticeships and traineeships, can provide students with practical skills needed for their chosen careers. Additionally, the government can collaborate with industry to forecast future skill needs, offer financial support for retraining or upskilling, and streamline the process for employers to hire skilled workers from overseas. This is crucial as there may be surpluses of skilled workers in some sectors and shortages in others. By prioritizing reskilling and aligning workers with future-facing industries, the government can organically address skill shortages.

In conclusion, the labor market is evolving significantly, necessitating alternative policies that focus on vocational education, flexible pricing, and reskilling. These strategies can better equip individuals with the skills needed to succeed in the workforce and make education more affordable and accessible. In light of the labor market’s challenges, the adoption of these alternative policy options is crucial for fostering a resilient and adaptable workforce capable of meeting the demands of a changing job market.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.