Almost one year ago to the day, millions of names, phone numbers and even passport numbers of Optus customers were accessed by hackers in one of Australia’s biggest cyberattacks ever. Cybersecurity has been a growing concern amongst the rise of technology and its involvement with everyday life, especially with how much sensitive information we store and entrust corporations with, and the Optus breach served as a fresh reminder of the risks. If the personal details of the 10 million Optus customers compromised, such as their drivers’ licence numbers and physical addresses, reach the hands of nefarious actors, the possibilities to exploit the information are wide-ranging, including further crimes such as identity theft and fraud. The potential ramifications of such confidential details being released only makes the inadequate protection and enforcement surrounding cyberspace a more pressing issue.

In another attack on Medibank last year, 10 million more customers and their medical details were jeopardised. The criminal had accessed Medibank’s network through stolen credentials used by a third-party IT service provider, further obtaining other Medibank systems’ credentials. Customer specific information such as codes associated with diagnosis and procedures were accessed, in addition to further customer claims that were associated with terminating pregnancies, mental health issues and drug and alcohol use. In response, Medibank had to increase their call centre staff by 300, with an emphasis in their Cyber Response Support Program that provided further security measures to customers that called them. In a cyber event timeline published by Medibank, they asserted their focus to pinpoint customer support and establish confidence in their data confidentiality, and increase the strength of their security systems.

Understanding the desires and motives of cybercriminals can help to identify what to protect and subsequently establish tailored preventative measures. Often, there is a financial goal behind the attack, whether it is retrieving data to sell on the black market, or stipulating money directly by holding data for ransom, such as the hackers who demanded $15 million AUD from Medibank (which the firm refused to pay). These demands stem from a variety of motives that can be broadly categorised into purely financial, egotistic and revenge based. Aside from monetary gain, most cybercriminals have some history with the firm targeted as an ex-employee or have negative relations such that they feel the need to compromise that company’s data. These threat actors may want to prove that the company cannot function without them or cause as much damage or embarrassment to the firm so as to fulfil their own self-esteem. As Optus’ breach had involved a ‘skilled criminal [who] had knowledge of Optus’ systems’, an ex-employee with that specific knowledge would not be out of the question.

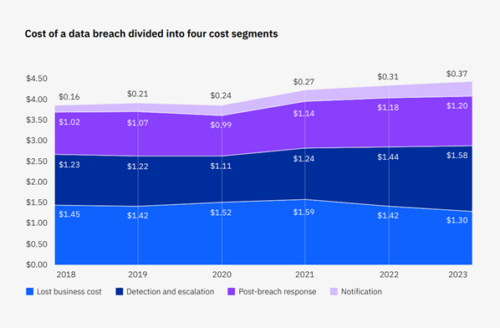

Despite the increasing sophistication and frequency of these cyberattacks, Australia’s regulatory regime has not kept up to manage these risks. In recent years, companies and organisations have seen breach after breach that has compromised customers’ digital identities and payment details, not only potentially derailing hundreds and thousands of customers’ individual livelihoods, but costing organisations and the economy millions of dollars. According to IBM, the average cost of a data breach has grown by 32% in the last 5 years, representing AUD $4.03 million lost in 2023 due to varying costs. Some have suggested that these attacks have only been possible due to the country’s slow-walking attitude towards modernising the data management, security and privacy systems that underpin the modern digital economy, whether it be in the public or private sector.

Source: IBM Security, 2023 (measured in USD millions)

Looking at Optus’ response to their cyberattack reveals a lack of organisation and preparedness that left their 10 million affected customers in the dark and to fend for themselves. While Optus is to be commended for disclosing the breach as early as possible, Optus customers who were dealing with the fallout of their identity documents being compromised had no streamlined framework to secure their identity and protect important details such as their bank savings and credit rating. For example, many customers looking to update their insurance or banking details reported difficulties in doing so, having to rely on a compromised driver’s licence waiting to be replaced, which required a written notification from Optus verifying that the request was genuine.

The inadequacy of the response system to cyberattacks and data breaches is not a surprise to those who have paid attention to Australia’s business cybersecurity landscape in recent years. A 2019 review of the identity theft response system commissioned by the government found a system that was ‘either non-existent or performing poorly from a citizen’s perspective’. The report found that there was no national approach and relied on old, antiquated standards which provided insufficient protection for the digital age. In fact, the main player in response to cyberattack and identity breaches for customers was IDCARE, a charity which buckled under the weight of customer enquiries and requests following the Optus data breach.

Cyber Security Minister Clare O’Neil has described Australia as being five years behind the world on cybersecurity (Source: ABC News)

There are signs however that businesses and governments have recognised their cyber vulnerabilities and its associated risks. In the past few years, statutory agencies responsible for cybersecurity such as the Australian Signals Directorate and the Australian Cyber Security Centre have seen significant funding increases that should allow for improvements in capability to further protect and deter cyberattacks from occurring. Meanwhile, businesses are expected to invest more than $9 billion over 10 years in cybersecurity protection not only to comply with new national security requirements but to protect from even greater losses incurred due to service outages and recovery costs. This sentiment is corroborated by increasing business concern surrounding the growing danger of cyberattacks as a business threat, underscoring the need to prioritise further investment in cybersecurity protection.

While Australia has finally begun to take the risk posed by cyberattacks seriously, the road ahead is far from smooth sailing, and there are difficult conversations that need to be had on the strategies we use. A controversial but pivotal topic in the discussion of improvements to cybersecurity methods is the concept of government surveillance on the internet. Government surveillance of the web, whilst certainly an effective tool to deter cybercrime to some degree, often encroaches upon the privacy of web users. Any expansion in government surveillance on the internet should be proportional and reasonable relative to the improvement in accuracy at which governments can assess cybercrime threats. Essentially, we need an appropriate level of internet surveillance, for an appropriate level of cybercrime. Beyond the ethics and privacy concerns of government surveillance, there are practical reasons too for more caution about the level of surveillance. Research has shown that an excessive amount of government internet surveillance would cause the acceptance of government surveillance by internet users to decrease and the potential for a defiant online user base to rise. This resistance exhibited by users would not only include encouraging circumvention of online government surveillance (e.g. VPNs), negative media outlook, and claims to human rights violations, but it would also create fertile ground for future cybercriminals to establish themselves in defiance of the government’s increased control over the online medium, thus worsening the problem. This can’t mean anything good for small and large businesses alike, which is why balance and respect of user privacy is so important if such an approach is taken.

Alternative solutions also include the improvement in specifically the cybersecurity of businesses. An example of this would be improving damage control by companies when they are hit by cyber attacks through the legislation of compulsory cyber insurance. Studies have claimed that cyber insurance can be the difference in the survival or bankruptcy of an SME (small and medium enterprise) as it can provide vital cash flow for when they are hit by a cyber attack. To bolster this point, studies into the importance of cybersecurity for companies in the financial sector particularly stress the consideration of cyber insurance. They state that this is due to the development of new technologies such as cloud based solutions and big data, which create a range of new cyber security concerns that need to be considered and mitigated. Thus, in order to ensure the protection of contemporary businesses, cyber insurance must be given due consideration by businesses and authorities.

Unfortunately, strengthening our nation, our businesses, and our people against cyber attacks will be a long journey with much uncertainty ahead. This is in part due to the rapid evolution of the digital and socio-political climate, and their implicit effects on the complexity of cyber attacks. New innovations such as AI or increased funding to digital espionage by less friendly governments are all factors that could accelerate the complexity of these attacks. In the face of the changing conditions in the digital world, governments and the private sector must work together to make the digital world a safer space for users.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.