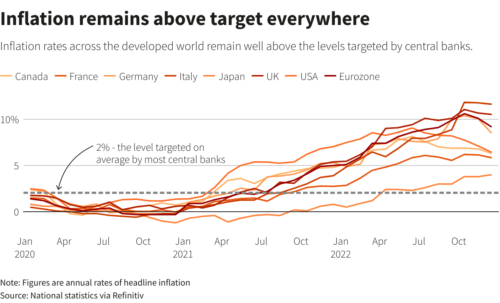

Grappling with double-digit inflation during the late 1980s, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand pioneered the practice of inflation targeting, setting a target of 2% in 1990. Since then, the 2% inflation target has become a common goal for most central banks, and inflation has mostly stayed within target. However, since 2021, the world economy has experienced a resurgence in inflation that central banks are struggling to tame. This begs the question of whether high inflation is here to stay. What does a future with structurally higher inflation look like? What are its resultant consequences and policy implications?

In recent times, the world has seen several fundamental changes that are placing structural inflationary pressures on long-term inflation. These factors can be split into the 3 Ds: demographics, deglobalisation and debt.

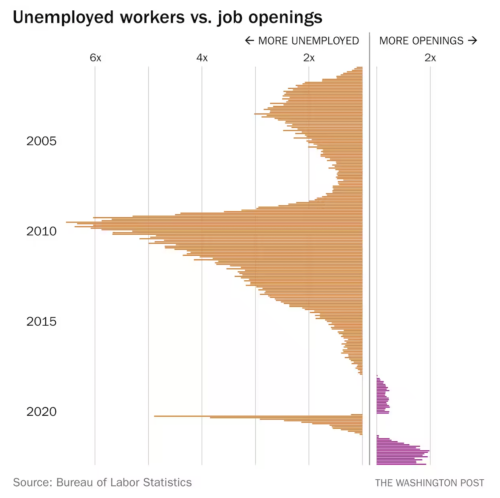

The aftermath of COVID-19 has left unprecedentedly tight labour markets across advanced economies, threatening to accelerate their ageing populations and subsequent inflationary pressures. The early retirement of baby boomers combined with stalled migration has also contributed to tighter labour markets, as the absence of migration imply a disproportionate rate of labour force outflows to those entering. Not only will this place greater pressure upon governments to fund social services amongst a shrinking tax base, but will also place inflationary pressure on bargaining power and wages as the labour supply struggles to keep up with increasing demands for goods and services amongst the retired population.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (The Washington Post)

As the pandemic and geopolitical instability have exposed the vulnerabilities of globalisation, there has been a concerted effort among many countries to build resilience and security into their supply chains, known as ‘deglobalisation’. While decades of globalisation and interconnectedness have lowered trade barriers, consumer costs and inflation, a reconfiguration of global supply chains may increase prices. As governments around the world mandate that infrastructure and capital projects be made with locally-sourced inputs, domestic producers stand to reap the benefits of deglobalisation. They face diminished competition from foreign producers and greater pricing power, which contributes to the increase in inflationary pressures that are likely to prevent inflation from substantially declining in the long-term.

The rising system-wide leverage experienced by most economies in recent decades continues to raise the spectre of structurally higher inflation. Not only has government debt skyrocketed as a result of the massive scale of fiscal stimulus employed during the pandemic, but private debt from corporations and individuals has also reached new highs. As governments issue bonds to borrow money, they consequently increase the money supply, which can lead to higher interest rates, ‘crowding out’ the private sector and stoking the inflation fire. Meanwhile, households may be willing to tolerate higher inflation if they believe it can reduce the real value of their debt. All of this is complicating the ability of central banks to control inflation through monetary policy tightening schemes, such as increasing interest rates. If central banks struggle to return inflation to target, and markets cannot foresee any pathway back, this risks entrenching expectations of structurally higher inflation.

Source: Reuters

Inflation often seems to have minimal impact on our lives, with the cost of items rising incrementally to the point where it is often not noticed. Therefore, many wonder what the cost of structurally higher inflation truly would be, considering that an extra 100bps per year seems quite innocuous. However, even small moves in inflation can significantly impact the purchasing power of consumers materially over time, particularly those in the lower to middle income streams.

By owning assets, higher income earners often have a degree of insulation from inflation. Asset prices likely rise at rates stronger than inflation over time, therefore ensuring that the wealth of asset owners is less eroded by the impact of inflation. However, for lower and middle income households who have far more of their wealth generated by income rather than through asset price appreciation, their wealth can be far more impacted by inflation. Over recent decades, wages have been unable to keep pace with inflation, despite inflation being within the target 2-3% range. Therefore, in a structurally higher inflationary environment, we expect real wages would feel even greater pressure from inflationary forces than what currently occurs. The diverging impact of real asset price appreciation but real wages decline will only heighten the growing trend of income inequality that has been observed over the last two decades, likely further entrenching those with lower incomes into their weaker financial positions.

Beyond real wages decline, lower income individuals are ultimately the worst affected by rising prices as well. While the rising cost of staple goods (such as food and energy) are often easier to absorb with a higher income, lower income individuals have to face impossible choices to either reduce consumption of necessary products or experience significant financial hardship. The disproportionate impact of inflation on lower incomes would only be heightened in a structurally high inflationary environment. As the staples such as rent, groceries and utilities form the core of inflation, rising inflation inherently is driven by these core products. Therefore, it is likely that lower and middle income individuals will not only have a greater gap in wealth to their higher income peers, but will also face greater risk of being unable to meet their core needs by purchasing staple goods. These clear diverging impacts have been best exemplified by the United Kingdom over the last twelve months. While the wealthy have been largely insulated from the worst of the cost of living crisis, surging energy and food prices have greatly weakened the standard of living for the poorest British people. Limiting inflation therefore remains fundamental to maintaining a higher standard of living across the populace.

Oftentimes, both inflation-related solutions and problems can occur when governments intervene. Domestically, their tools can reduce inflation, such as increasing taxes on higher income brackets. However, this may not be politically practical. Therefore, countries in recent times have chosen to interact with each other to affect inflation. This is prevalent in the current world political climate, where the Russo-Ukrainian war has caused the global economy to deglobalize. An example of this would be the economic sanctions imposed by the European Union against Russia in response to their aggression towards Ukraine. This has resulted in the prevention of entities within Europe from importing and exporting key products from Russia.

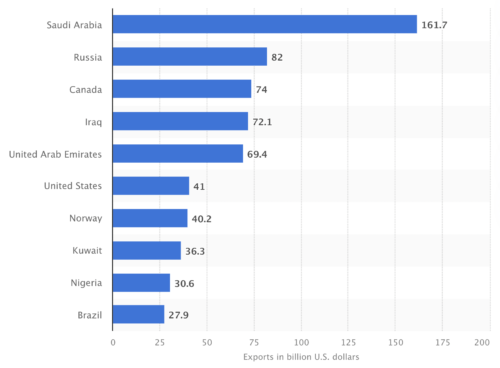

Countries with highest value of crude oil exports 2021

Source: Statista

The most notable of these being fossil fuel resources like crude oil. The graph above displays that Russia was the second largest exporter of crude oil in 2021, which means that this conflict has resulted in a supply shortage of that commodity. This has further led to an increase in transportation costs worldwide, increasing the price of all products, thus leading to supply-side inflation. Deglobalisation has also occurred because trade is now heavily reduced between Russia and the rest of Europe due to these sanctions, and countries which imported most of their crude oil must now either provide it themselves or find alternative suppliers. The USA and Australia were also participants in these sanctions and also suffered the effects of supply-side inflation.

A solution that involved both of these countries along with other members of the International Energy Agency was to release sixty million barrels of oil from emergency reserves and into the global market to alleviate rising inflation in 2022. In releasing more oil into the global economy, they alleviate pressure on global suppliers to increase supply to match high demand and hamper inflation rates.

Furthermore, the USA in particular has moved to strengthen its relations with Saudi Arabia and other alternative oil exporters in the Middle East in hopes of increasing their trade volumes of imported crude oil to further alleviate the limited supply. A deal has been struck between the two nations, though a lack of clarity from Saudi officials about whether they have engaged in similar interactions with the Russian government has only heightened tensions between both countries. This highlights an important point about governments and economic goals: governments with political differences that must interact to create solutions for economic problems must put such differences aside to solve them efficiently.

In short, the speculation of the three factors affecting structural inflation pressures implies that inflation will be higher in the future. This will carry numerous social and economic problems in the future such as rising income inequality and less-than- proportionate wage rises. Thus, while government decisions have contributed to inflation in the past, it is important to realise that if the political differences of different nations are put aside, they could encourage greater globalisation. This could serve as a driving factor in slowing down the transition to this new economic environment of structurally higher inflation, or perhaps prevent it altogether.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.