The growth of East-Asian economies has been regarded as an economic miracle, as these countries started off as stagnant, slow-growing economies in the 1950s, and are now some of the most important economic powerhouses in the world. For reference, East Asia currently accounts for 20.5% of the global population and makes up US$40 trillion in GDP.

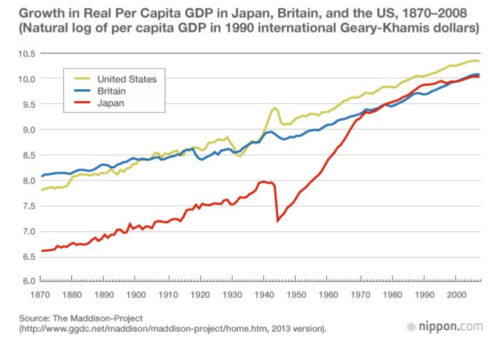

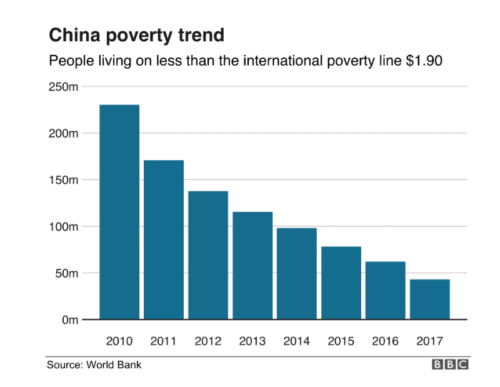

China started off as a communist economy with GDP per capita one-fifth of the world average in 1950, but managed to increase its GDP by 4 times from 1979 and 1999 and lifted 800 million people out of poverty, and is now regarded as the second-largest economy in the world. Japan faced the aftermath of the post-World War 2 collapse, but quickly recovered and developed its manufacturing sector and restructured its labour and investment policies to become one of the most prosperous countries in East Asia. Singapore followed suit in economic growth from these two economies, transforming from an island nation with no natural resources in the 1960s to one of the largest global business and trading hubs in Asia.

This article will look at long-term trends in economic growth in these three economies and draw links to existing economic theories.

Singapore

Singapore has been regarded as a success story amongst Asian economies and is one of the Four Asian Tigers along with Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea.

Singapore began as a slow-growing economy in the 1950s, facing a range of economic problems including racial riots, poor infrastructure, and low levels of economic growth, and its unemployment rate was estimated to be around 9% in 1959. At that time, Singapore was also known for its high crime rates and opium dens and had a GDP per capita of around $US500 in 1965. Singapore has faced a range of challenges in becoming a self-sufficient economy, gaining independence from Malaysia in 1965 and facing the loss of 20% of its jobs from Great Britain’s withdrawal of troops, but has shown strong growth since its separation.

Singapore particularly experienced high economic growth from 1965 to 1973 as the government introduced policies to increase the production of capital goods, with real GDP growing at an average annual rate of 12.7%. Singapore also decided to attract foreign direct investment from multinational corporations, creating export-dominated and labor-intensive growth and reducing its reliance on other Asian neighboring countries for its growth. In 1972, a quarter of manufacturing firms in Singapore were owned by joint ventures or foreign companies, receiving inflows of investment from countries such as the United States and Japan (Economic History of Singapore).

During the 1970s to 1990s, Singapore saw strong economic prosperity and growth in the technological and trading sectors, making use of its advantageous geographical location as a coastal city to operate trading ports for domestic and international markets. Despite facing recessions from oil shocks in 1973, Singapore still managed to maintain high levels of economic growth, averaging 8.7% from 1973 to 1979, and 8.5% from 1979 to 1981. However, Singapore has become more dependent on trade to support its nation, with correspondent Anthony Faiola from the Washington Post mentioning that “when world trade boomed, Singapore’s seaport at the crossroads of East and West became the Chicago O’Hare of freighters and supertankers” (Faiola, 2009).

Since the 1980s, Singapore also saw developments in other industries including the financial and business sectors, as it started to assert its position as a leading international trading hub. This is attributed to the highly developed infrastructure and politically stable environment implemented by the Singaporean government, and the reduction of trade barriers and operation of free trade, as its international trade was valued at triple its GDP in 1988. Singapore competed with the likes of Hong Kong and Japan as the leading Asian financial sector in the late 1980s, with the Singaporean banking and financial services sector accounting for almost 25% of the country’s GDP (Economic History of Singapore).

In the 1990s, Singapore continued to prosper as a global financial center, as Singapore became home to more than 650 multinational companies, as well as other financial firms from around the world. Singapore still saw high economic growth of 7-8% until the mid-1990s, but its GDP growth was mainly linked to increased growth in electronics, as communications and office equipment became more important to the Singaporean economy, increasing from 15% of exports in 1980 to 60% in 1995. Singapore’s GDP per capita also exceeded US$13,000 in 1990, as it grew faster than other developed economies such as Portugal and South Korea.

From the 2000s onwards, while Singapore has faced economic challenges such as the Global Financial Crisis, and the global pandemic, it is still continuing to see strong economic growth today, hitting 3.4% growth in the first quarter of 2022. Singapore is still seeing strong growth in the manufacturing industry, and the opening of domestic and international borders post-pandemic reinforces its importance as a global trading port. Seah Chiang Nee, a Singaporean journalist, mentioned that Singapore “has, like an invisible giant hand, lifted the bulk of a squalid population and moved it into the middle class” (Nee, 2012).

Japan

Japan on the other hand, represents one of the biggest modern financial riddles. Being the second largest economy in 1994, it found itself in the stagnation that lasts up to this day. As a result, minimal economic growth, constant fight with deflation, and enormous government debt are just some of the issues faced by the nation today.

Left with a depleted economy and 47% lower GDP after a devastating defeat in the Second World War, Japan urgently needed to find a way to transform its economy. Thankfully, US occupying forces led by General Douglas MacArthur had similar interests of demilitarization, leading to numerous political, social, and economic reforms being enacted to prevent Japan from the remilitarization of the state like Germany did after the Treaty of Versailles. The first step taken in that direction was a political reform that dismantled the Japanese Army and prohibited former military officers from taking any roles of political leadership in the new post-war government. Such a decision ensured that the new generation of leaders did not follow resentment of a defeat and instead looked at it as a new opportunity for growth. It was then followed by an economic restructuring, starting with a land reform designed to cut the influence of rich landowners who supported the war and looked towards Japanese territorial expansion. Furthermore, in an attempt to transform the country towards free market capitalist society, a number of laws were passed to break down big corporate conglomerates, better known as zaibatsu. And while today we can see that all of the listed transformations aligned with Japan’s development, at that time they were focused on preventing the country from reverting back to the regional military mogul.

However, as the Cold War started to emerge and many East Asian countries fell to the communist movement, the United States understood that the best way to confront growing socialist ideas in Japan was to reconsider their occupational policies and instead concentrate on the economic recovery of Japan. Thus, the “revert course” began to address the issues of the ineffective tax system and took measures towards controlling inflation. And while those efforts had great intentions, low buying power of the population and shortage of raw materials challenged any further development. An unexpected opportunity to address those issues emerged in 1950 with the outbreak of the Korean war. Being in close proximity to Korea, Japan became a major supply hub to the UN forces, boosting the production capabilities and lifting many industries from the stagnation.

After the end of the war and proving that the system was established enough to operate on its own, occupational forces left Japan in 1953. From that moment on, the country has become a major producer of many electronic goods exported worldwide. Furthermore, as foreign investments started flowing in, the economy began transforming towards its status quo. By the late 1970s, Japan had converted into a technological and industrial powerhouse with companies like Sony, Toshiba, Mitsubishi Electronics, Toyota, and many others becoming major suppliers in the North American and European markets.

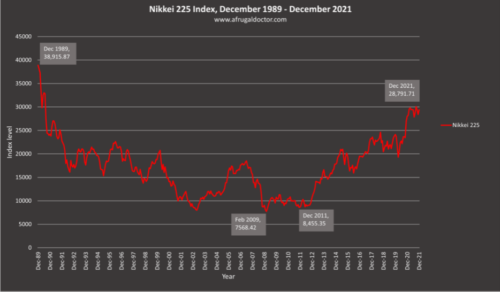

However, policies that once led Japan to its success, later turned into a strain. Cheap credit, large tax breaks, and overall “administrative cooperation” that was supposed to assist and protect local corporations led to ineffective operational activities with hundreds of billions of dollars in bad corporate debt. Finally, in the late 1980s, the asset bubble burst, leading to one of the longest recessions among the developed economies. Known as a “Lost decade” due to the fact that it had taken more than 10 years to pull the economy to the pre-burst numbers and implementing a new term for such long lasting process called “L-shaped recession.”

Prior to the collapse, the government attempted to fix issues within the economy with various fiscal-stimulus measures. However, this led to an overheating of the economy and the subsequent policy measures, mainly interest rate hikes and the introduction of a consumption tax, did not have the same degree of effectiveness as envisioned by policy makers.

As shown by the above graph, the Nikkei 225 index faced a heavy crash in 1991 and the reasons were the same as in any other overheated economy: inflated real estate and stock prices, uncontrolled money supply, and overconfidence in the future. As the financial markets started collapsing, the real estate markets followed suit, with a 15.5% decrease in residential and industrial land prices. Since land was often used as a collateral, together it resulted in downturns in profits, plummeting stock prices, and further increase in bad debt. But because many highly leveraged firms and investors continued defaulting on their obligations, banks had to take overwhelming losses. Bankruptcies of 3 major financial institutions: Yamaichi Securities, the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan, and the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, quickly became symbols of the failing economy and proved that the impact of recession would be bigger than anyone could think of.

30 years later, the consequences are still present within many of the major economic sectors. However, one of the biggest challenges to the modern Japanese economy has been the decline in its population and the implications of this will be explored later in the article.

CHINA

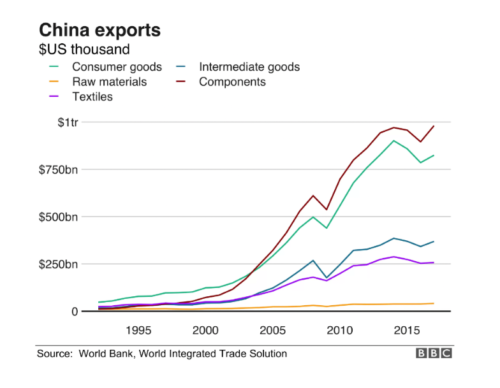

Known as the “workshop of the world’’, the Chinese economy underwent dramatic transformation subsequent to its reopening to foreign investments in the late 1970s. According to figures by the London School of Economics, when the Chinese economy opened up to the rest of the world, its exports were valued at approximately $10 billion making up less than 1% of world trade. Only within the span of 7 years they hit $25 billion in 1985, and currently stand at around $3.5 trillion accounting for around 15% of global trade (Harrisson and Palumbo, 2019).

Chinese poverty rates have also decreased significantly with education being a key factor to provide a secure future. Education rates have been rising rapidly, with 27% of China’s workforce expected to obtain a university degree education by 2030, matching the level of education in Germany as of now, according to projections by Standard Chartered.

However, moving forward the Chinese economy faces multiple hurdles that seem to be restricting its rate of growth. Some of these factors include an increasing wealth divide between urban and rural communities, a need to shift away from a export based economy towards a consumption based economy, political rifts leading to trade wars, tight global demand factors alongside the pressures of an ageing population.

This year, from July onwards, the country experienced a decrease in consumption and output which was caused by a multitude of factors. The strict zero-Covid policy implemented by the Chinese Communist Party has sharply slowed down growth as lockdowns and other restrictive measures have limited purchasing opportunities for the domestic population and restricted supply chain movements. The Chinese Central Bank has cut lending rates in recent times to attempt to revive demand. Youth unemployment is at a record high of 20% coupled with the Chinese property sector taking a major hit as mortgage boycotts storm the country. Homebuyers have been losing faith that their unfinished housing projects will be completed. As a result, property investment dropped 12.3% in July alone. (Miller, 2022)

Another aspect to consider has been that China’s rapid rise has not been environmentally sustainable. With an emphasis on manufacturing and exports, the Chinese economy has ramped up its carbon emissions. The Chinese economy accounts for 27% of global carbon dioxide as well as being the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases with per capita, recently passing the European Union (World Bank).

Moving forwards, the Chinese economy will have to discover and implement strategies to combat its environmental misgivings as well as tackle other constraining factors that have slowed down its economic output in recent times.

In terms of similarities and differences between these three Asian economies, there are definitely some key factors which arise when compared. Singapore’s beginnings as a former British colony contrasts with the beginnings of the Chinese economy under a Communist revolution and Japan’s rebirth after World War 2 with the significant support of America and its economic thought. When observing Singapore’s period of rapid growth between 1965 and 1973, similar ingredients such as attracting foreign direct investment, increasing the level of exports and the supply of cheap labour resulting in labour-intensive growth, also seem to be central in the Chinese economy’s development in the late 1970s. However, Singapore’s growth accommodates some stark differences compared to China and Japan due to its transformation from such initiatives to a more nuanced economy with a backbone of providing financial and business services. Technology has also been central to Singapore’s development with it being named the best digital transformation environment in Asia, drawing parallels to Japan’s electronics sector.

When investigating further into the downturn in the Japanese economy of the early 1990s, cheap credit and unsustainable levels of leverage seem to be dire warning signs for the Chinese economy of late, with a very similar credit crunch affecting the recent downturn fuelled by turmoil within the country’s real estate and property development markets right now. The levels of pollution and environmental unsustainability currently resulting from China’s activities can be noted as unparalleled amongst the other economies and it seems to be a distinct problem that has to be addressed soon.

What does the future look like?

Altogether, even being in the same geographic region each country faces different types of challenges to overcome in the near future. Singapore being a small city-state within an island may have problems that may seem small when compared to those of neighbouring nations, but the influence they have are big enough to make the whole country worried. One of them is the fact that much of its activities and growth is dependent on major world economies. Taking the recent Covid-19 pandemic as an example, we could see how recessions around the world have led Singapore to a slowdown in many of its activities, resulting in -4% GDP growth. For that, an uncertain future in many of the largest world economies and increasing regional instability are two of the biggest factors for a country to consider in its future policies.

Japan, on the other hand, has most of its struggles originating internally. Its declining population is one of the most prominent issues, as each year the nation shrinks by more than 600,000 people and where almost 30% of the nation are beyond the age of 65. Put together, this means that each working age person will have to support more societal functions than the previous generation. Thus, the government will have to find a way to increase the productivity of the whole country. Requiring a lot of investment, it will put an even bigger toll on the Japanese government debt, which is already the world’s second highest in terms of relationship to GDP. With that said, Japan does not have a choice but to transform its economy and introduce a plan of actions to counter these issues, otherwise it will have no other option but to go down.

In the case of China, one of the biggest challenges to the nation will be addressing the prevalence of income inequality- having one seventh of the world’s population makes it particularly difficult to make such growth equal among all segments of population. However, there are also new challenges on the horizon that need to be addressed. One of the biggest problems is very similar to its neighbouring Japan: the ageing population. Result of the “one child policy,” in recent years it became clear that there needs to be a plan addressing potential population collapse.

In conclusion, all three economies have grown over the last seven decades, originating from backgrounds of decolonisation, revolution and post-war resurrection. The attraction of foreign direct investments whilst simultaneously capitalising on cheap labour and manufacturing has enabled these countries to experience non-linear growth. Although Japan may have potentially peaked already due to an over-reliance on debt and inconvenient demographics, it still hosts a booming electronic goods sector that services the whole globe. China has been one of the biggest economic success stories of this past generation, but it also has impending demographic problems that it will have to deal with alongside a need to shift towards an economy centred around complex services as well as domestic consumption. Singapore has arisen to become one of the financial hubs of the world, adopting many technologies to ensure it has sustained economic growth since its transformation. All three economies have benefited from a cycle of industrialisation, mobilisation and globalisation and it will certainly be interesting to observe the directions in which these economics and countries pivot into the future.

References

Hu, Z., & Khan, M. (2019). Economic Issues 8 — Why Is China Growing So Fast? IMF. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/issues8/index.htm

Crawford, R. J. (1998, January). Reinterpreting the Japanese Economic Miracle. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1998/01/reinterpreting-the-japanese-economic-miracle

Drucker, P. (2014, August). Behind Japan’s Success. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1981/01/behind-japans-success

The cautionary tale of Japan: Why an L-shaped recession is so undesirable. (n.d.). NPR.org. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2022/08/19/1118521017/the-cautionary-tale-of-japan-why-an-l-shaped-recession-is-so-undesirable

Hays, J. (n.d.). ECONOMIC HISTORY OF SINGAPORE | Facts and Details. Factsanddetails.com. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Singapore/sub5_7c/entry-3782.html#:~:text=In%20the%201970s%20through%20the%201990s%2C%20Singapore%20experienced

Crawford, R. J. (1998, January). Reinterpreting the Japanese Economic Miracle. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1998/01/reinterpreting-the-japanese-economic-miracle

Drucker, P. (2014, August). Behind Japan’s Success. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1981/01/behind-japans-success

East Asia and the Pacific | Economics. (n.d.). World101 from the Council on Foreign Relations. https://world101.cfr.org/rotw/east-asia/economics#reforms-launch-china-s-rise-to-global-economic-superpower

Economic slowdown: China urges push to boost sluggish economy. (2022, August 17). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-62571995

Harrison, V., & Palumbo, D. (2019, September 30). China anniversary: How the country became the world’s “economic miracle.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-49806247

internationalbanker. (2021, September 29). Japan’s Lost Decade (1992). International Banker. https://internationalbanker.com/history-of-financial-crises/japans-lost-decade-1992/

Japan Recession | Is Japan In a Recession Right Now? (n.d.). Capital.com. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://capital.com/japan-recession-inflation-weak-yen-stimulus

Singapore economy grows 3.4% in Q1, slower than previous quarter. (n.d.). CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/economy-singapore-gdp-grows-q1-2022-mti-advance-estimates-2623476

The cautionary tale of Japan: Why an L-shaped recession is so undesirable. (n.d.). NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/19/1118521017/the-cautionary-tale-of-japan-why-an-l-shaped-recession-is-so-undesirable

The World Bank. (2022, April 12). The World Bank In China. World Bank; The World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview#1

United States Department of State. (2019). Milestones: 1945–1952 – Office of the Historian. State.gov. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/japan-reconstruction

Zhou, P. (2019, July 10). How Did Singapore Become a Leader in Global Commerce? ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/singapores-economic-development-1434565

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.