The origins of tertiary education can be traced back to 1808, where the first university in the world, The University of Bologna was founded in its namesake, where it still exists today. The concept of university is derived from the Latin term “universitas”; these institutions, both ancient and recent of origin, are the gateways which all scholars and future engineers, physicists, analysts and doctors pass through in order to achieve their potential and serve their communities. But as time has progressed, obtaining an undergraduate degree from university is not the hallowed certification it once was, guaranteeing its holder access to any and all important arenas of their respective fields.

The University of Bologna Source: The Heritage Foundation

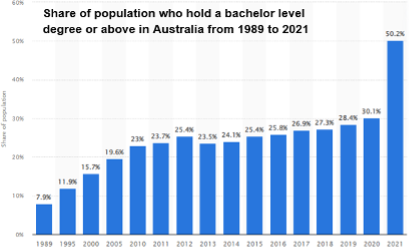

In more recent years, there has emerged an inequality in the hiring rate of those who graduate with a bachelor’s degree and those who continue on with their studies to expand their knowledge in masters’ programs and doctorates. Participation in universities is at its highest in the last two decades. In Australia, over 11 million people reported having a vocational or tertiary qualification, a 19.8 percent increase since 2016. Moreover, the level of tertiary education enrolment rates continues to rise as the risk of unemployment and absolute wage earning prospects fluctuates in an upward trend, as it is more and more likely that climbing up the job ladder will only be possible with, at the very least, a bachelor’s degree. Recently, a new trend has emerged where a masters’ degree is seen as the “new bachelors’ degree”.

With universities awarding almost 760,000 masters degrees in 2014-15, visible wage differentials between those who have continued with university after earning an initial degree and those who did not, and an ever rising quantity of student debt that is not fully analyzed due to lack of sufficient wage data, one would venture to think that this trend of superiority of masters degrees has always been prevalent. The “parchment ceiling” is a concept referring to the fact that, today, in many careers and industries, having a bachelors’ degree is vital to getting promoted, indicating that everyone, from all socioeconomic backgrounds and regions, will very likely opt to pursue tertiary education if they want to succeed in their chosen field.

However, in the past, the process of simply attending a university and obtaining a degree of any sort was retained solely to the hands and prospects of a very sheltered and elite group of people – namely those who could afford it or those with enough family status and influence to gain them the means of access into those hallowed halls of learning.

The ordinary person could not afford to go to university, indeed, even finishing the final years of school education was a contested decision as it clashed with the opportunity cost of lost work hours and wages earned, whether this work was in a factory or a butchers’ block, a typing pool or the agricultural fields. Yet gradually, with worldwide changes that arose due to the industrial revolution, relative world peace, a growth in money availability, as well as the need for offering services, the demographics of who – or rather, who only – attended universities changed drastically.

The United States was the first nation that constructed a mass higher education system, spurring other countries to begin gradually expanding their own higher education arena to include not just the wealthy elite but catering to the masses, in order to raise the potential of every person interested in partaking of higher education and surmounting their career and wage earning prospects. Interestingly, in more ancient and traditional institutions such as The University of Oxford or The University of Cambridge, it was only the inception and growth of the science faculty that led to them changing their traditions away from solely educating young “gentlemen”, and instead switching to educating young persons interested in pursuing specific vocational purposes.

Source: The University of York.

Mass and elite higher education, though fundamentally altered now from its nature and purposes of as recent as the 18th-19th centuries, still demands a lot of its students, and despite granting degrees to many different demographics, the fight to actually include demographics such as women, indigenous people and people of colour has been a long and hard one, and the battle is still being waged, though on much subtler, quieter grounds. With this as the background, the earning of degrees, once an unthinkable achievement for those who were not allowed near the elitist halls of education like Oxford, is now quite proliferated, especially due to globalisation. However, this illustrates the changing nature of any field, as the increasing number of people flocking to higher education has rendered bachelors degrees a common achievement. Though still laudable and important to achieve, bachelor’s degrees have fallen in status since the time of gentlemen and beadles, morphing from elite certifications into a necessary and basic qualification to enter and succeed within most professional fields.

As taught in the vast majority of undergraduate Economics classes, theory suggests that it is a good time to pursue postgraduate study during a recession. This is due to the opportunity cost of time spent out of the workforce is lower.

Research has found that those graduating during recessionary periods earn less for at least 10 to 15 years while working more than those who graduated during periods of economic prosperity. Furthermore, recession graduates are less likely to be married, more likely to be childless, and adopt a higher death rate at middle age. Whilst there is little evidence to suggest that the difference in income levels between well- and ill-timed graduates differs significantly from 0 in the long run, the question remains whether the impact on wealth levels would differ significantly, given the time value of compound investing, with the earliest years having the greatest impact. This is something that has not been as closely analysed.

With regards to mortality, Ruhm (2000) found that deaths are initially lower for recession graduates, although this is driven entirely by fewer fatal car accidents and is likely the result of recession-induced reductions in traffic. However, a deviation in the trend began to arise for those in their late 30s. “By age 50, one extra death per 10,000 was registered for every percentage-point increase in unemployment at graduation, affecting males and females similarly” , with heart disease, lung cancer, liver disease, and drug overdose being the leading causes. Researchers believe that the two likely reasons behind the bleak(er) outlooks for graduates of recessionary times is hysteresis and/or being introduced to the labour market where one is permanently stuck on a downward-shifted economic trajectory.

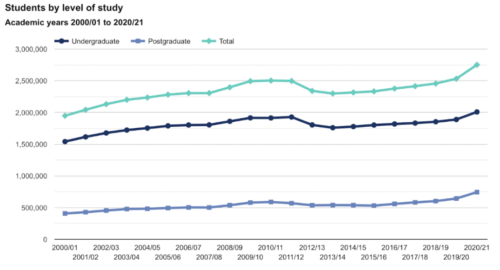

So, do we actually experience an uptick in the number of people pursuing postgraduate degrees during recessionary times? In short, yes. We have seen time and time again that this is indeed the case in the recessions of the ‘80s, ‘90s, early and late ‘00s, and we’ve begun to see it over the past few years too.

Postgraduate numbers increased by 18% (87,590) between the years of 2007/08 and 2010/11. In contrast, the three years preceding the crisis saw an increase of just 4% (19,356) across the UK. The number of first year postgraduate taught students [in the UK] increased by 16% compared to 2019/20. Prospect’s survey also found that “16% of final-year students had lost their jobs as a result of the UK’s pandemic response.”

Source: Unknown.

With the advancement of tech, increasing international competition, tougher psychometric testing, and a seemingly ever-increasing number of application stages, successfully securing a job offer is becoming increasingly difficult – even during economically-prosperous periods. This is having a larger general impact on what is seen as a hurdle requirement and what is perhaps indirectly required so as to differentiate one candidate from the next. The marginal benefit and differentiation of a bachelor’s degree between future labour force participants falls as the number of people attaining a bachelors (or higher) increases. Looking beyond jobs that require a doctorate (i.e., a surgeon or an astrophysicist), we are seeing that students are having to take out more loans, more time away from the workforce (foregoing income in the short term), delaying time to climb the property ladder, etc. to further their tertiary studies in order to increase their job prospects. Not only does this negatively impact those who have only attained a bachelor’s degree, but also highschool graduates (and dropouts).

Degrees aren’t just a development of understanding and knowledge, they also act as a signalling device. Degrees are inherently costly to fake. But when the market is flooded, the value of the signal provided to employers is lessened. When everyone has a degree, how is the market to tell one graduate from another on the one-page sheet of accomplishments provided during an application?

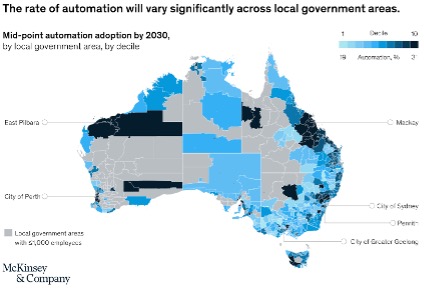

As graduates enter the job market, two challenges they face are job automation and credential inflation. As the nature of work changes, there will be professions that flourish while others become extinct. In 2019, the OECD Employment Outlook projected that more than 36% of jobs in Australia face a significant or high risk of being automated in the next 15 to 20 years. Also in 2019, Mckinsey & Co. estimated 25-46% of Australian jobs could be automated by 2030.

Source: McKinsey&Co.

Amongst the most vulnerable professions are:

Source: MIT Sloan Management Review

When navigating a changing world, graduates may wish to consider jobs where both the core skill set, and how it is delivered to consumers are not under significant threat. Hands on professions that require problem solving such as Electricians and Plumbers, as well as medical orientated professions are expected to be the most insulated from automation.

Credential inflation is another concern graduates face entering the job market. This refers to the devaluation of educational credentials as more people acquire them to outcompete their peers. George Mason University economist Bryan Caplan likens it to being in a cinema where people want a better view of an exciting movie (not Thor: Love and Thunder…), resulting in them standing up. Those behind them also stand up to avoid missing out. Soon, everyone in the cinema is on their feet, begging the question, wouldn’t it be better if everyone just sat down? The concern is that many educational credentials are primarily acting as signalling devices, rather than a means of upskilling and preparing students for the workforce.

Source: Statista

In Australia, as of 2022, 97% of ICT job postings require a bachelor’s degree or higher. In direct contrast to this, Google offer career certificates to train people who wish to enter the technology industry but do not have time for the traditional university route, indicating that many businesses don’t necessarily think a degree is essential for certain entry level roles, it is simply convenient for them to make it a requirement when screening applicants.

Moving forward, those entering the job market should be weary of the threats of automation and credential inflation, however, they can also make the most of the opportunities that will arise from innovation and progress. After all, at the end of the day, every act of creation is first an act of destruction.

In the long run, it will be interesting to see how this follows on into Masters, MBAs, and ultimately, PhDs. With recessions historically falling roughly every decade, we can assume that the pace with which we expand our postgraduate studies will continue to grow into the future.

We need to invest more today to prove our abilities and differentiate ourselves from the next applicant than our parents did. Our kids will no doubt have to invest more tomorrow.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.