The Call That Changed Everything

May 28, 2025

Editor(s): Yoon Lee

Writer(s): Mitchell White, Ruicheng Wang, Max Chen

Introduction

Once optional tools for long-distance meetings, video calling services have become essential to everyday business, social, and educational interactions — transforming interconnectivity and collaboration across contexts. Platforms like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet were relatively unknown or niche prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the globe online. Previously adopted mainly by tech or cross-border firms, early iterations were often slow and clunky. But as lockdowns took hold, these services rapidly evolved into polished, versatile tools. Today, even as the pandemic recedes, video calling remains embedded in hybrid work, education, and social life — though not without growing concerns around privacy and fatigue.

Brief History of Video Calling

Whilst video calling services feel like both a new and old advancement simultaneously – to many’s surprise the first “video calling” service was developed in 1964 by AT&T’s Picturephone. However whilst a fruitful idea, technology at the time simply was not advanced enough to allow any functional use. The next major development came with Skype launch in 2003, which leveraged the invention of the internet and the rapidly improving computing process power. Skype’s model was to use the internet to allow users to make free video and voice calls. With the simplistic user interface for the time – Skype became a hit with families and international callers. Around this time other market players began to emerge – Cisco WebEx (formally WebEx) launched in the early 2000’s and tailored their product towards businesses by focusing on conference calls that enable collaboration.

AT&T’s Picturephone. Source: Britannica

Despite this, video calling still remained a secondary tool. Slow and clunky interfacts were quickly becoming outdated, and unreliable audio and visual syncing and high latency still saw many potential users put off. Mobile video calling services was a large development in the early 2010’s with FaceTime debuting in 2010 and Google Hangouts in 2013. These widely successful products highlighted an appetite for video calling services. Yet the notable difference in use cases (FaceTime and Google Hangouts were used mainly in a casual setting), highlighted consumers’ hesitations and belief that video calling services are not suitable for more important occasions such as business meetings, schooling, etc.

Facetime by Apple. Source: cnet.com

Why the Hesitation in Uptake Before COVID-19?

Before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the globe online, video calling struggled to find utility in people’s everyday lives. Whilst the technology was available and seemed promising – it was seen as an unreliable alternative to in-person meetings. With only tech firms, cross-border entities, and remote workers in niche industries seeming to utilise its convenience. Poor user interface design, lagging video quality and frequent connectivity issues saw potential users pass-up on the technology as they did want to rely upon unproven technology, especially when handling important matters.

Moreover, general technology prior to COVID-19 was also less advanced, such wider technological limitations slowed the adoption of video calls. Bandwidth constraints, especially in rural or developing regions, often resulted in high latency calles or even no connection at all, harming the user’s experience and ultimately sentiment towards video calling.

One World’s Crisis is Another Platform’s Opportunity

As COVID-19, and its associated implications, swept across the world in the outset of 2020, video calling swiftly transformed from a niche tool into a global necessity. In April 2020, demand for video conferencing soared, epitomised by a 500% increase in customer activity for both web and video conferencing services. Indeed, platforms like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and more, would experience an exodus of users who, in pre-pandemic times, would have relied on frequent face-to-face meetings. Zoom perhaps embodied this involuntary boom of digital conferencing the best; its active user base exploded from just 10 million in December 2019, to an almost unfathomable 300 million by April 2020. This explosive growth extended beyond user growth, and even into contemporary vernacular. Phrases like “zooming” became a household verb — impressive for a company that was obscure to most people just a couple months back.

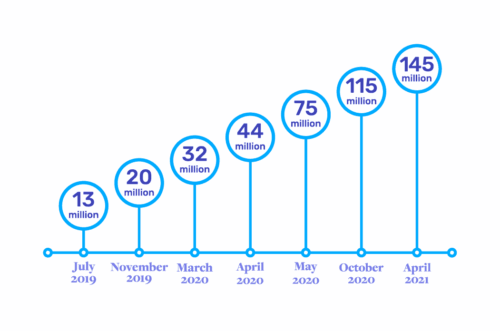

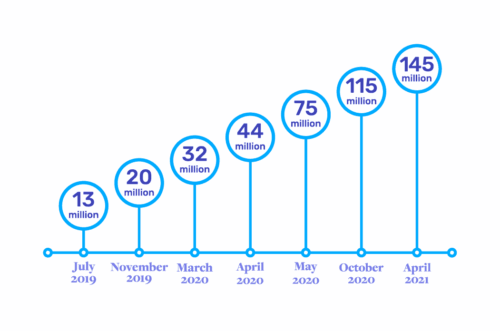

This rally towards online conferencing was also enjoyed by others. Skype, a withering giant once synonymous with video chat, peaked at 40 million daily users (a 70% jump from pre-pandemic times) — non-trivial, yet paling in comparison to the monstrous figures of Zoom. Other tech giants also scrambled to enter this new market. Microsoft Teams, first introduced in 2017, rocketed in usage as offices went virtual, with some key milestones including 13 million users in July 2019, to 75 million in May 2020, to an unseemly 145 million by April 2021. Google’s entrance into the online conferencing race under its eponymous Google Meets platform was no less impressive. The service experienced a 30-fold increase from pre-pandemic to April 2020, surpassing 100 million daily meeting participants in the same month.

Infographic of Microsoft Team’s skyrocketing presence. Source: TomTalks

Yet curiously, even as the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic had passed in late 2022, the video conferencing user base has seemingly sustained consistent growth — albeit muted compared to its explosive heights in early 2020. Valued at $10.6 billion in 2022, the industry’s CAGR of 12.6% suggests that online meetings are here to stay. Indeed, what started as an emergency stopgap has crystallised into a lasting digital backbone for communication.

The Meeting Room is Dead. Long Live the Meeting Link

Video calling has permeated every corner of daily life — not just as a necessity, but as a default. When offices closed overnight, companies scrambled to recreate the workplace virtually. Zoom replaced boardrooms, Teams became the new water-cooler, and hallway chats turned into scheduled calendar invites. For many, the flexibility and autonomy of remote work proved not only sustainable, but preferable. In education, over 1.2 billion students were locked out of classrooms at the height of the pandemic. Teachers had to pivot fast, mastering screen sharing and microphone troubleshooting as much as their own subject matter. And while online learning had its limitations, it endured. From pyjama-clad uni students to language learners dialling into classes across the globe, virtual classrooms are now part of the fabric. Even socially, people found ways to stay connected, with video calls becoming venues for birthday parties, hangouts, and even weddings. Physically apart, but virtually present — a new normal born out of necessity, but sustained by convenience.

A couple getting married in front of virtual audience. Source: New York Times

All Zoom and No Rest

However, as the world has slowly embraced video meetings into daily life, cracks in the digital utopia have begun to show. The phenomenon of “Zoom Fatigue”, a form of mental burnout, has cropped up almost as quickly as the video conferencing revolution itself. The fact that online conferences lack the intimacy of traditional social cues, such as the constant need to look at oneself, and others, has been found to be unnatural for an extended period of time, thereby causing stress and exhaustion. This growing awareness of videoconferencing’s negative side-effects have encouraged companies to institute meeting-free days, or even physical get-togethers later on in the COVID-19 lifecycle. Certainly it was a poignant reminder that even as video platforming has helped bridge the physical gaps once thought untenable, the pressures of maintaining an unceasing digital presence carried a deleterious human cost — an ironic fatigue from the very tool designed to keep us all connected.

Post-COVID: A Hybrid Future and Evolving Market Dynamics

As the world has gradually transitioned out of pandemic restrictions, the ever changing landscape of video calling has not reverted to its pre-covid norms. Instead, it evolved; now a hybrid model of interaction, blending in-person and remote communication and continuing to dominate as a preferred method of communication across workplaces, education and social life. While the innate need of mass video call has declined, the habits and virtual infrastructure built during the pandemic have left a lasting imprint on how we communicate today.

COVID is over, but virtual meetings still dominate the workspace. Source: Display Note

A key trend post pandemic has been the rise of more specialised and integrated tools. Platforms like Zoom have moved far beyond basic calls, layering on enterprise grade features such as automated transcriptions, breakout rooms, and collaborative whiteboards to stay embedded in the corporate workflow. Even Slack, which traditionally focussed on asynchronous chats, evolved and introduced “Slack Huddles” during the pandemic to enable quick, informal video and audio connections. Meanwhile, Microsoft Teams has capitalised on its deep integration with Office 365, evolving into a full scale productivity hub rather than just a meeting app.

Simultaneously, the sector has undergone a battle for dominance, with stronger players absorbing market share while others have struggled to stay relevant. Skype, once touted as the face of internet calling, has seen significant decline and has largely faded from public view. Similarly, Cisco Webex, has lost ground to more user-friendly and agile competitors. This consolidation of weaker players in the industry has narrowed user choice but sharpened the sector’s focus on innovation and integration.

However, new challenges continue to emerge in this developing market.

Privacy and security remain top concerns, with government and enterprise users raising the bulk of the concerns. Trends such as “Zoom Bombing” during the early pandemic enkindled increased scrutiny towards video calling companies and demand for better encryption and moderation tools.

Monetisation also remains as a friction point. Zoom, once the darling of pandemic era productivity, experienced a meteoric revenue increase of over 300% in 2021, reaching $2.65 billion. However, growth decelerated to 55% in 2022 and further to 7% in 2023, with revenue totalling $4.39 billion.The question for these video calling companies remains: will they be able to convert their free users into paying subscribers or sell premium features in a competitive and saturated market?

Video Calling’s Future Lies Beyond the Screen

The video calling industry has come a long way from the days of clunky Skype connections and awkward delays. What started as a niche tool for corporate use has metamorphosed through the cocoon of a global pandemic into an everyday necessity. Nowadays, Zoom is a household name, Google Meets becoming a familiar sight for G-suite users and Microsoft Teams successfully embedding itself into the corporate workplace.

Now, as the world rebalances between office desks and kitchen tables, the video calling space finds itself at a crossroads. The rapid pace has slowed, but the demand hasn’t vanished. Instead, it’s matured.

The next frontier might not be more pixels or smoother video calls; but immersion. Think AI powered meeting summaries, real time language translation, or even holographic coworkers similar to Star Wars through the magic of Augmented Reality glasses. Meta is already exploring this with its Orion project, blending the virtual with the physical in wild new ways. Whether that future feels thrilling or slightly dystopian depends on your point of view.

XM reality’s new Hololens 2

However, one thing’s certain: the video call isn’t going anywhere. It’s no longer just a stopgap for when we can’t meet; it’s been woven into how we work, learn, and connect. The race now is to make it better, smarter, and maybe even fun again.

Investors are picking up on the signal too. The global video conferencing market is projected to surge from $37.29 billion in 2025 to $60.17 billion by 2032, driven by a shift towards hybrid work and a hunger for technological advancement. The money flowing in is a clear vote of confidence: there’s still plenty of room for fresh ideas, bold innovation, and the next big disruptor.

In short, video conferencing didn’t just survive the pandemic, it grew with us. And now, it’s entering its next era.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated

with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne.

Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers,

printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne

do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy

of information contained in the publication.